Ian McLellan: the August 1993 pipes|drums Interview from the Archives – Part 1

We met with Ian McLellan on August 12, 1993, at a pub near Glasgow University’s Pollock Halls, a few days before the 1993 World Pipe Band Championships, a competition he would not compete in for the first time in decades. As with most pipes|drums Interviews, we waited until he was clear of competing so that he might share his thoughts more freely.

McLellan retired from the Strathclyde Police Force in 1992, at age 55, after 30 years of service. At the time, the band did not allow guest players. That is, every member was a serving police officer, so staying with the band he guided to 12 World Championship titles, and famously six in a row (1981-’86), was not an option.

McLellan would be a judge at the 1993 Worlds, and the change to the pipe band world was substantial. After the streak was broken in 1987, McLellan’s Strathclyde Police would go on to win another four straight, until Field Marshal Montgomery wrestled away the prize in 1992, “The Polis” placing second.

![Ian McLellan (right) judging the Grade 1 1993 World Championship with Andrew Wright, Bellahouston Park, Glasgow. [Photo pipes|drums]](https://www.pipesdrums.com/storage/2026/01/Field_Marshal_Montgomery_Worlds_1993_03.jpg)

Before or after the recorded interview, we wanted to confirm the spelling of both his first and last names. He was clear then that it was “Iain MacLellan,” and that’s how it appeared in the final printed piece, which he vetted before publication. (Similar to an authorized biography, we allow interviewees to have the final edit of full-length pipes|drums Interviews, and he did not change the spelling.)

In November 2025, for whatever reason, we contacted him again to ask about the spelling, since it continues to be spelled differently in various articles and online. He confirmed it’s “Ian McLellan” and that he made it so after his official given name, “John,” could be confused with the numerous John Mac/McLellans in solo piping. No matter; just an interesting aside, at least to us.

Ian McLellan passed away on December 3, 2025, at the age of 88. His funeral was on December 19, 2025, at a packed Glasgow Cathedral, where the UK’s piping and drumming illuminati gathered, as well as those watching online.

We’re pleased to bring readers the pipes|drums Interview from the Archives with Ian McLellan, which we will publish in two parts.

Part 1

Introduction

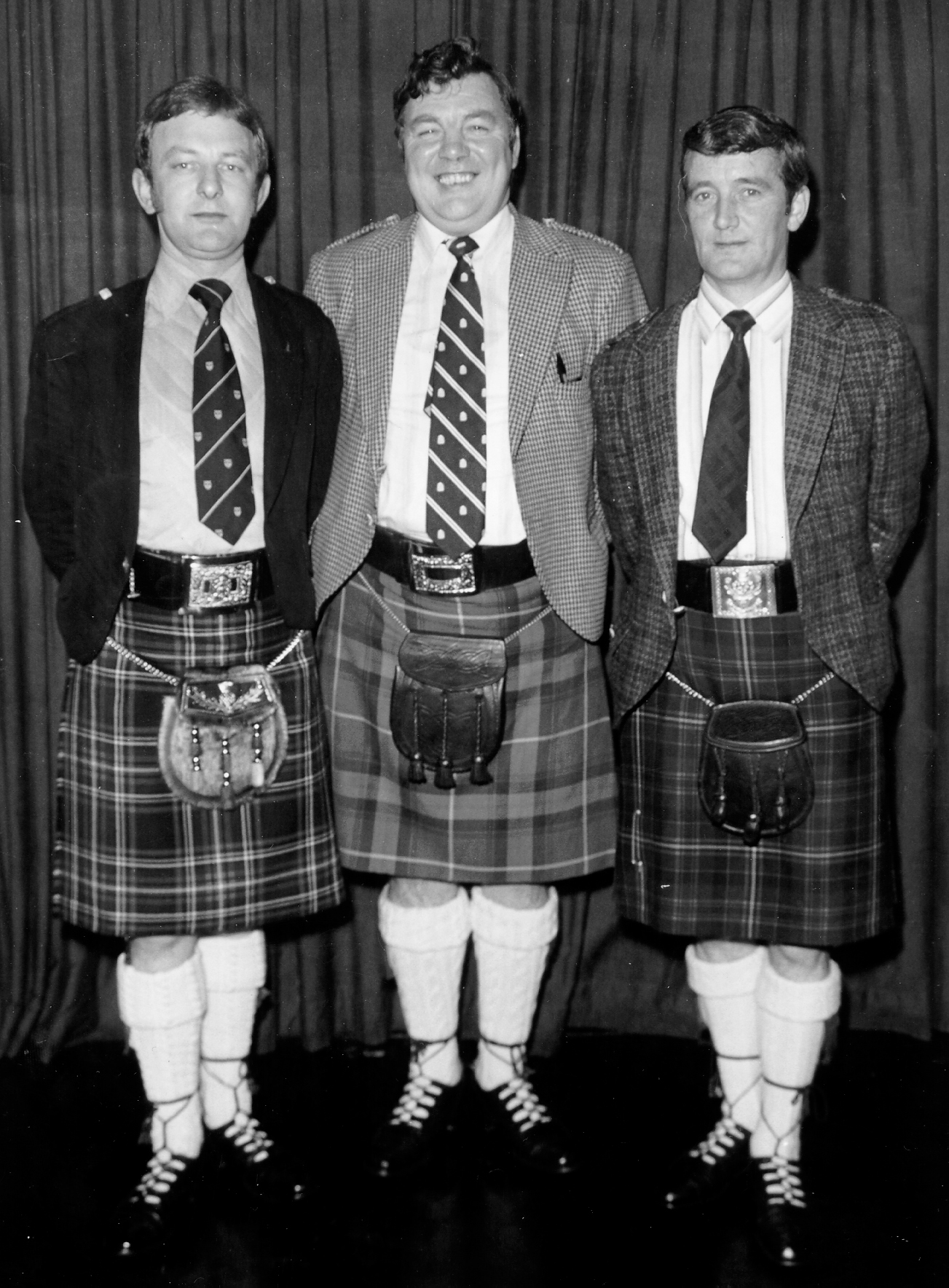

![Ian McLellan, August 12, 1993 [Photo pipes|drums]](https://www.pipesdrums.com/storage/2026/01/McLellan_Ian_Aug_1993_03.jpg)

If fame in piping is measured by the competitions one wins, McLellan had already, by 1986, secured his place in Chapter One of The History of the Pipe Band. By that year, he had led the Strathclyde Police Pipe Band to a record eighth World Championship, and the sixth in a row.

By the time he retired from the force in 1992, after serving the maximum period of thirty years, McLellan had amassed an astonishing twelve World titles and thirteen Champion of Champions awards for best aggregate record over a season, eleven of those titles in succession. Add to the mix his sterling solo record in light music over the short five years he competed: two Silver Stars at Inverness, and the Former Winners’ MSR at Oban, and his stature becomes even greater.

And great, too, is lan McLellan’s personality. He is one of the rare few from the pipe band game who seems not to have a foe. For the duration of his career, and even today as an adjudicator, he can always be found having a laugh with anyone who engages him in conversation, and he readily parts with any “secrets” he has gained in his twenty years as pipe-major of the Police.

Ian McLellan’s peers are as few in number as his foes.

McLellan was born in Clydebank, outside the city of Glasgow, in 1937. His first pipe band was the 214th Boys’ Brigade Company in 1949. As he progressed in piping, he joined the Grade 1 Renfrew Pipe Band in 1955. He stayed with that band under Pipe Major James Healey until 1958, when he was called to complete his required two years of National Service in the Argyll & Sutherland Highlanders. With the Argylls, he studied Piobaireachd and light music with Pipe Major Andrew Pitkeathly.

After finishing his service in 1960, lan McLellan rejoined Renfrew, which by then was under the leadership of Tom Anderson, who now lives in Rexdale, Ontario. That band finished second twice at the World Championship, and McLellan cites Anderson as having a profound impact on how he would ultimately lead the Glasgow Police.

In 1962, McLellan joined the Glasgow Police force and played under Pipe-Major Angus MacDonald of South Uist, until Ronnie Lawrie took over the top job at the turn of the decade. In 1972, McLellan was appointed pipe-major, and four years later, at the World Championships in Hawick, the band won its first world title in twenty-five years. But even after winning twelve Worlds and two Silver Stars, McLellan regards his 1982 British Empire Medal as the high point of his piping career.

He lives now, as he has for the last twenty-four years, in the Glasgow suburb of Bearsden. He is married and has two daughters and a granddaughter.

On August 12, 1993, we completed the following interview with Pipe-Major Ian McLellan, BEM, an exceptional leader and an absolute gentleman.

pipes|drums: How are you enjoying your retirement?

Ian McLellan: I’m thoroughly enjoying it, but I wouldn’t say it’s been a retirement because I’m probably busier now than I’ve ever been. I seem to have less time to myself since retiring than I did when I was actually in the police force. I thought my main activity after retiring from the police would be playing golf, but unfortunately, that hasn’t worked out. I’ve been really busy with teaching at summer schools, teaching bands, and travelling abroad, and since January, I’ve been working with Joe Noble in The Band Room, getting that part of the business off the ground.

pipes|drums: Only the most uninformed bandsman would not rank you as the greatest competitive pipe major of all time. How do you answer when asked what the secrets to the Strathclyde Police Pipe Band’s success were?

Ian McLellan: I don’t think there was any secret. It was mostly hard work. During the wintertime, we spent an awful lot of time on the practice chanter. I would say about half of that was me teaching all of the pipers on a one-to-one basis. That was one of the main factors in the success of the band. Most mornings every week, I would have one or two pipers on a one-to-one basis. Obviously, there are other factors as well, like musical interpretation and how the tunes would be played and things like that. The band has been known over the years for having very consistent tone, and that also was one of the main factors.

Initially, when the band started to have success, the tone that the band had was one of the main reasons that it was successful, because the tone was maintained throughout the season, possibly because we blew pretty heavy reeds, and I believe that created stability to the tone and helped to maintain it throughout the season.

“One of the main things I looked for when I auditioned a player was whether he could blow a good tone. If he couldn’t blow a good tone he would get nowhere near the band.”

pipes|drums: When you had a new piper come to the band, how long would it take before he was ready to play?

Ian McLellan: There would be a conscious effort to get him into the style of playing that the band has settled on. I’ve seen some of the pipers that we have taken into the band who have taken at least two years before they ever played in a competition. One of the main things I looked for when I auditioned a player was whether he could blow a good tone. If he couldn’t blow a good tone he would get nowhere near the band. So we would take a player into the band who technically might not be perfect, but who had the potential there to work on him.

pipes|drums: Consistency in blowing was number one?

Ian McLellan: Yes, if they didn’t have that, I wasn’t interested because if you’ve reached the age of being a mature person and you’re in the police force, I don’t think there’s much hope of learning to blow a good tone after you’ve reached that age. I think tone is a thing you learn when you’re very young. If you’re playing among good players, then you’re going to learn what the sound should sound like and really educate yourself to play that type of tone. I find that I have taken pipers into the band who have not been as good blowers as I would have liked them to be, and at the end of the day, they never made the grade because they couldn’t blow the required sound that I was looking for.

pipes|drums: What was your role in designing the Warnock chanter?

Ian McLellan: About two years after the first Warnock chanter came out, Jim Warnock asked my views on it. I felt that the first one was too high-pitched, so we worked on a new mandrill. Warnock chanters are injection moulded, and we worked on a new internal mandrill for the inside bore, and eventually we got the sound and the pitch that we were looking for from it.

pipes|drums: But, at the same time, your band still played Sinclair chanters. Without getting into the politics of it, do you think the Sinclair’s the best chanter for pipe bands?

Ian McLellan: Well, one of the main reasons I stuck with the Sinclair was that I knew the chanter and I knew how to set it up. I had worked with it with Willie Sinclair, and in fact I don’t think Willie Sinclair was all that enamoured with some of the things I was doing to his chanter. If you know how to work with Sinclair chanters, you will get a nicer sound than you would from a manmade material.

pipes|drums: Not everyone knows that the Strathclyde Police Pipe Band experienced dramatic changes in the pipe corps from 1985 on, from the loss of John Wilson and Angus J. MacLellan as pipe-sergeants to an almost total revamping of the pipe section on several occasions. How were you ever able to maintain a standard from year to year?

Ian McLellan: 1987 was really when all of the changes started to take place. In ’87, we went down to eleven pipers, and that was as low as the band had been in quite a number of years. We knew at that time that there were other good-calibre pipers within the force who weren’t playing in the Strathclyde Police Pipe Band, but played in other bands. So, I made it known to the Chief Constable at that time. I went to Japan for three weeks on a promotional tour for the Strathclyde region, and when I came back, there were five new pipers in the band.

pipes|drums: The Chief Constable took care of it for you?

Ian McLellan: I think they were given an offer they couldn’t refuse!

pipes|drums: Is it policy now with the Strathclyde Police as a force that any piper who comes into the force has to play in the band? Did that change in 1987?

Ian McLellan: No, nobody’s actually forced into joining the band or coerced into the band. In 1987, we were reaching the point where we were either going to be a force to be reckoned with in the coming years, or the whole thing was going to go down the plug hole – competition-wise, I’m talking about. We’ve been very fortunate over the years; all the Chief Constables and the actual Strathclyde region during my term as pipe-major have always been very supportive. They see the band as advertising not only the police force but also the region. I’ve been abroad, and people have admitted to me that they would never have known where Strathclyde was if it hadn’t been for the Strathclyde Police Pipe Band.

pipes|drums: We’re hearing some more modern compositions and arrangements come out of the band under Harry McAleer’s direction. By contrast, Strathclyde Police, under your leadership, was known for being somewhat reserved in tune selection. Was that a conscious decision on your part?

Ian McLellan: I don’t agree with your statement about not using modern tunes. The last two or three years, we used some very innovative tunes, like compositions by Michael Grey and Bruce Gandy and a lot of other Irish tunes that bands are playing also. Maybe it was the way that I arranged them or orchestrated or phrased them, in possibly the more traditional idiom rather than a more free-flowing idiom that some of the other bands play.

pipes|drums: Would that be because of your own personal musical preference, or were you thinking of the prize a little bit?

I think possibly it’s just my own style of playing that has crept into it because I found it very hard to get myself into this kind of roundish style of playing, especially for the Irish tunes. It wasn’t really in my nature to play like that. The medley Harry McAleer has submitted for the Worlds has a lot of nice tunes in it, but possibly, with Harry being an Irishman, he finds these tunes easier to play than I do! [laughter]

pipes|drums: What was your strategy when putting together a medley?

Ian McLellan: When you look at the Strathclyde Police medleys over the years, there has been a set pattern. I never really noticed that until someone pointed it out to me during one of the summer schools in the States. He said, “You make up all of your medleys in the same way,” and I looked at it, and I said, “Aye, you’re right enough. I do make them all up the same way.”

You need a tune to march into the circle with, then invariably we went on to strathspeys and reels and slow airs, and then hornpipes and jigs, or jigs and hornpipes, and it seems to have been that format for quite a few years. When I look back at the medleys that we had over the past few years, the only change was in the early ’80s when we marched into the circle and then played slow air. Possibly, my ideas have never been as innovative as Bill Livingstone’s, as far as the way he has handled jigs and hornpipes and things like that. But I always have felt that if you try to do things like that, other people will say, “Oh, he’s just copying them.” I always just say this is the way I do it and I’ll just keep it that way. And it worked to a certain degree! [laughs]

pipes|drums: How do you feel about the medley requirement? Did you prefer the MSR?

Ian McLellan: Funnily enough, when the medley event started, I enjoyed the medleys because it was so easy to make them up. There were so many tunes to pick from that bands weren’t using. And as the years went on, it became more and more difficult because you were trying to get something that was both fresh and good. It’s no good playing something fresh if it’s not musical. Why play something new just because it’s new? It was becoming more difficult over the years to try to put together a good medley. In fact, sometimes I would hear a record, maybe the 78th or the Simon Fraser, and I would think, That’s a cracking tune. We would play it in the medley because I like the tune, and the guys in the band liked the tune. If it sounds nice and it’s pleasing to the ear, then why not play the thing?

But at the end of the day, I was very much a march, strathspey & reel man because I used to love playing big MSRs. Basically, that’s why the band always played them so well, because we enjoyed playing them. If you asked the Strathclyde Police Pipe Band what they preferred playing, they’d say the big march, strathspey & reels.

Although there are a lot of nice things happening in the medley competition, I feel that a lot of the lower-grade bands, especially the lower-grade bands, are losing the art of playing the big march, strathspey & reels because they’re concentrating so much on the medley. When they come to play the big MSR they don’t seem to be able to handle it anymore. Now, I don’t know whether this is because they don’t practice enough, or whether they don’t put enough thought into it, or whether the youngsters that are coming through on the scene now have been brought up with so much accent on the medley that they don’t know anything about march, strathspey and reels. You can hear them playing march, strathspeys and reels, but it’s just straight down the middle, there’s no strong weak medium weak accent coming through at all. It’s sort of like, Let’s get this over with and get back to the medley. It makes me worried that they’ll lose the art of how to play these things the way they should be played.

pipes|drums: Do you think that this is a result of too much innovation in medleys or the kitchen piping phenomenon?

Ian McLellan: I think possibly that kind of thing is coming through a bit too much in some of the medleys. The 78th Fraser Highlanders can handle that type of thing because they’ve got the expertise, they know how to handle it, and they know how to transform back onto the big march, strathspey & reel, because the talent is there to handle it. But the bands that don’t have that talent try to emulate what the Grade 1 bands are doing, insofar as the medleys are concerned. When they go onto the big MSR they’re completely lost. But the powers that be can fix that by stipulating that every second contest should be an MSR contest.

It doesn’t matter if it’s a major championship or just an ordinary run-of-the-mill contest. If you have a medley this year, your contest will have an MSR next year. That’s how to fix it, because then you will have to concentrate more on the march, strathspey & reel.

pipes|drums: There seems to be this idea, mostly from either non-pipers or bad pipers, that the MSR is not entertaining to the crowd.

Ian McLellan: Well, if a march, strathspey & reel is played properly, it is going to be entertaining. It’s either that or lose it altogether, and I would hate for that to happen.

pipes|drums: You come from an army piping background with the Argylls. How much has piping changed since National Service was stopped?

Ian McLellan: You don’t have the same number of pipers coming through the army now, obviously, because the National Service guys from civvy street aren’t going in and doing their two years. When I was in the Argylls, I had been in the Renfrew Pipe Band before I had gone into the army, and there were four of us from the Renfrew band who went into the Argylls at the same time. There was myself, Alex Clapperton, who was a piper from the 214th Boys Brigade Pipe Band, the same Juvenile band I played in, and we both joined the Renfrew band at the same time, and we both joined the army at the same time. Shortly after that, there was another piper called Tommy MacPherson who came to the Argylls, and another chap called Seamus Fraser. In fact, at one time there were about six pipers who had all gone through the Argylls.

pipes|drums: That was the Renfrew Tom Anderson had?

Ian McLellan: Aye, Tommy was pipe-major of the Renfrew when I came out of the army. When I went into the army, it was a chap called Jimmy Healey who was pipe-major. I was very impressed with Tommy because I think he’s one of the finest guys I’ve ever worked under. At that time, he had a really strong pipe corps the year after I came out of the army, and if that band had kept together, it could actually have gone places, and maybe the whole history of the pipe band scene would have changed.

But I left and joined the police, Tommy MacPherson and Jimmy Dow went and joined the Muirheads, and another chap who was in the band, Willie Fortune – he later joined the police. I always felt that if that pipe corps had stayed together for another two or three years, we would actually have been a really successful band in Grade 1.

![Tom Anderson judging at the 2011 Cambridge Highland Games in Ontario. [Photo pipes|drums]](https://www.pipesdrums.com/storage/2024/12/Anderson_Tom_CambridgeGames_July2011_-31_med.jpg)

Ian McLellan: Aye, before I went to the army, we had been second at the Worlds for two years running, and we won the European Championship two years on the trot, but that was under a guy called Tommy Shearer, who emigrated to America after he had had the band for only two years. He moved to Bridgeport, Connecticut. He was another really good player. So, the Argylls had quite an association with the Renfrew Pipe Band over the years. In fact, Andy Pitkeathly, who was the pipe-major of the Argylls at that time, composed a four-parted march, and he was looking for a name for it, and we said, “We fancy playing that in the Renfrew Pipe Band,” and he said, “Well, just call it that ‘The Renfrew Pipe Band.'”

pipes|drums: Why don’t we talk about your solo career . . .

Ian McLellan: [laughs] . . . It was a pretty short one!

pipes|drums: Short, but impressive. Didn’t you win two Silver Stars?

Ian McLellan: Aye.

pipes|drums: That’s pretty good going.

Ian McLellan: Not bad.

pipes|drums: Who gave you your grounding in light music?

![Andrew Pitkeatly, with his trademark pipe, judging at Crieff Highland Games, 1984. [Photo pipes|drums]](https://www.pipesdrums.com/storage/2020/10/Pitkeathly_Andrew_Crieff1984.jpg)

I was never a piobaireachd player before I went into the army but when I came under Andrew I learned about twelve altogether, and he actually wanted me to stay on in the army and go on the Pipe-Majors’ Course, but during about my second year in the army, Angus MacDonald, who was pipe-major of the City of Glasgow Police Pipe Band at that time, wrote to me and asked if I’d ever thought about a career in the police service because of the police pipe band, and to me that seemed more attractive than staying in the army. If I hadn’t done that I would probably have gone on the Pipe-Majors Course.

When I left the army and joined the police, I came under Ronnie Lawrie’s wing, and he taught me a lot about the solo piping game; he was the one who really encouraged me to start playing on the solo platform. Until that time, I had never thought too much about it. I started competing in 1964, and the following year I won the Marches at Oban; two years after that, I won the Former Winners’ March, Strathspey & Reel.

For some reason, the band always had other engagements during Inverness, and I never really competed there until 1970. Then I won the Marches at my first go there and had quite a few other prizes at Inverness after that. But I was mostly successful at the indoor contests, like the Uist & Barra, the Scottish Pipers, the Edinburgh Police contest, and the Eagle Pipers.

I stopped competing seriously in about 1973. I found that when I took over the band in 1972, there was quite a lot of work needing to be done. There were quite a lot of guys nearing retirement age, and I sort of got rid of them quickly and got new guys in. In fact, the first new piper I got into the band was John Wilson. He was my first really good player. Jimmy Wark came into the band at the same time, and then another young lad, David Pirrie, who was a piper in The Guards, who had just joined the police, we got him, then we got Harry McAleer, and then it was just a kind of succession.

After that, I seemed to get all of the ones I wanted. Then, in ’75, when the five police forces amalgamated to become the Strathclyde Police, it meant that the City of Glasgow Police, the Lanarkshire Police and the Renfrew and Bute Police pipe bands amalgamated. But these two other bands had a very small number of police officers in them. Most of the others were civilians. From Lanarkshire, Barry Donaldson was the only one who joined. From Renfrew and Bute, I got two pipers, Jim Maclean, Sid Spence, and Charlie Simpson, who was a snare drummer, and Bob Edmondson, who was a bass drummer.

A pipe-major is a special breed of person. I think you’ve got to be a psychologist. [He rolls his eyes] You have to be able to know the pipers who can take the stick, and the others who go away in the corner and cry if you give them a row.

pipes|drums: There are only a handful of current or onetime solo pipers leading top bands these days: Terry Lee of SFU, Ian Duncan of the Vale, Bill Livingstone of the 78th, Hugh MacInnes of Power of Scotland. What importance does top solo experience have on being able to lead a band well?

Ian McLellan: Your own musical interpretation has a great deal to do with it, not that that makes you a great leader of men at the end of the day.

A pipe-major is a special breed of person. I think you’ve got to be a psychologist. [He rolls his eyes] You have to be able to know the pipers who can take the stick, and the others who go away in the corner and cry if you give them a row. If you’ve been a successful solo piper, obviously you know how to handle the music, and if you know how to handle the music, you’re going to do the same with your pipe band, getting them to try to emulate the way you play.

pipes|drums: There are bands with a real sense of style, and then there are bands that are just kind of grade one bands, good bands, good tone, but just sort of straight down the middle of the road. Do you think that a style comes across because there’s a solo player in charge who really knows how to finesse tunes?

Ian McLellan: I would think that would be a good argument towards it because I think it’s how you interpret the tunes. You can’t get a pipe band to go up there and play like a solo piper, and in fact you wouldn’t want them to go up there and play like a solo piper, it would sound dead, there would be no fire, no drive. At the same time, you’re not losing the phrasing so that it doesn’t sound absolutely straight. What also adds to it is the calibre of players that you have in a band. If you have players with good dexterity of fingering, it can make a tune sound faster than it really is by the nimbleness of how they handle the phrases.

pipes|drums: Your band had this rare combination of fingerwork, tone and expression. But some bands may not be great at tone, but they play really well together. How much do you think bands today are rewarded for unison? Should there be a preference given to tone?

Ian McLellan: It’s a funny thing, you know, because if you hear a band with a great tone, it makes you listen to them. And if you hear a band with a mediocre tone, you say, I don’t really fancy that too much, and to a certain degree, you switch off, especially if you’re a listening audience. If the band doesn’t strike up and hit you right between the eyes initially, you might not listen so intently as you would if all of a sudden, this sound just hits you and you think, “This is it, that’s what I’m looking for,” or, “That’s what I like.” Then you listen intently.

I would say possibly it’s unfair on the band that maybe doesn’t have the same impact with the tone, because there might be something in there that you’re missing if you’re not listening. And I hope that never ever happens to me if I’m adjudicating because I would like to think that I go out there and listen to what is going on, and if it’s an acceptable tone and a band is doing really well, musically, then I’d listen and give them credit for it.

pipes|drums: You must have heard of the reputation that Strathclyde Police had during the years the band dominated the scene: The sun always shines when they play; They always get a good draw at the Worlds; The judging is biased in their favour. How do you respond?

Ian McLellan: I just laugh. I suppose if you go back and look at the records, then as far as the good draws go, we have been very fortunate over the years with good draws. I’d say about 75% have been good and about 25% have not been so good. So far as the sun shining, I’ve played in some terrible downpours. People used to say to me after we came off, Your band sounds better in the rain than what it does when it’s dry!

pipes|drums: What about the judging? How would you respond if someone said, Oh, well, the judge always gives preference to the Strathclyde Police.

Ian McLellan: I think if you look back over the years at any band that has a run of success, judges will go for the form horses at times. That’s human nature, I suppose. But people used to say these things, and it never used to bother me. If you’re going to be winning consistently, you’re going to be playing well consistently. There’s going to be the odd day when you’ll come out and not be up to your usual standard.

Stay tuned for Part 2 of Ian McLellan: the pipes|drums Interview from the Archives, coming soon.

NO COMMENTS YET