Richness, depth, and a call for the music of old

The Highland Pipe and Scottish Society, 1750-1950

The Highland Pipe and Scottish Society, 1750-1950

by William Donaldson

Tuckwell Press, East Lothian, Scotland, 2000

Reviewed by Jim McGillivray

The Highland Pipe and Scottish Society, 1750-1950 is a startling book. It is deep and rich in its telling of the history of pipe music, and convincing in its argument that the piobaireachd of today has died a death attributable to those who most vociferously claimed to be saving it.

Its author, William Donaldson, is a piper and prize-winning social historian. Most of us have never heard of him. But he should be remembered from this time forward as the writer of one of the most significant piping publications to be produced in the last hundred years, if not ever.

Donaldson is a meticulous and ambitious academic researcher, gleaning from hundreds of published and unpublished sources the history of pipe music from the mid-eighteenth century until recent times. This is largely a study of published collections– who created or compiled them, how they came into being, and the broad and specific influences they had on piping and pipers. We learn about Joseph MacDonald’s Compleat Theory of the Scots Highland Bagpipe, with its implied notions that the playing of piobaireachd around 1760 was a much freer thing than it is today, that players were allowed to play embellishments as they saw fit and vary melody notes where appropriate. In this early chapter, Donaldson states a premise that will be repeated again and again throughout the book:

In Joseph’s time, then, “authority” was located in performance and not in the written score or its institutional sponsors.

This theme will be re-echoed in subsequent chapters dealing with the works of Donald MacDonald, Angus MacArthur, Neil MacLeod of Gesto, Angus MacKay, William Ross (not Willie), David Glen, Donald MacPhee and General Charles Simeon Thomason.

The book is full of the history around these collections, stories that many of us may have heard from the ‘old’ pipers around the games and gatherings in years past and thought apocryphal or lacking in evidence. For example:

“In the spring of 1820, Angus MacArthur, Donald MacDonald’s teacher, and former piper to the MacDonalds of the Isles, lay on his deathbed playing the practice chanter. By him sat John MacGregor III, of clann an sgeulaiche, piper to the Highland Society of London, pen in hand, copying down what he heard. Also present was musician and society painter Andrew Robertson from Aberdeen, one of the Society’s treasurers. MacArthur and MacGregor were being paid. Half a guinea a tune. Eventually, there would be thirty of them. And so the ‘Highland Society of London’s MS’ came into being.”

These kinds of anecdotes frequent the book, and are presented only with firm historical evidence. Donaldson relates rumours that the MacCrimmons may actually have had a written record of the music they taught, but he is careful to point out that not one shred of evidence exists to confirm this, though much material was destroyed over the years at Dunvegan castle.

But this book is much more than the history of our greatest music collections. It is also an argument for the apparent losses incurred when pipers set to paper what was once a vibrant and varied oral tradition. And it is a scathing indictment of the rigidity and restriction placed on piobaireachd by the early Highland Society of London and the Piobaireachd Society under its great pillar of power and influence, Archibald Campbell of Kilberry.

Indeed, poor Campbell, originally the lesser light of three Campbell brothers, is the villain of this piece.

The story heats up during the time of the Highland Society of London’s first competitions, which began in 1781. Before the days when piobaireachd music was etched in stone, Donaldson contends, tunes and interpretations were so varied that entire competitions could be run with the competitors all playing the same set tune. “In modern conditions,” he says, “this would be unendurably tedious,” because everyone would play the same setting pretty much the same way. Though sponsored by the Highland Society, the competion was in these days run by pipers. Variations in performance and score were the norm, grounds were repeated between later variations and competitors were allowed to tune in mid-performance, much like a modern orchestra might tune briefly between movements of a symphony.

All this changed just after 1800, when control of these major competitions fell out of the hands of what Donaldson terms “the performer community.” For nearly 30 years the Highland Society competitions were the responsibility of Sir John Graham Dalyell, a Society official who, it appears, did not like the pipes. (We are not told why a gentleman who hated the pipes so steadfastly ran a piping competition for three decades.) Under Dalyell’s leadership the competition was streamlined from three days down to four hours. Tuning either before or during the performance was banned, as were repetitions of the ground. The number of tunes played was reduced, and the whole affair was judged largely by local gentry who had little idea what they were hearing. Prizes most often went to the biggest names, the greatest technicians, or those whose success for whatever reasons suited the needs of the sponsors. In this way, says Donaldson,

“…a traditional, fluid and creatively flexible art form was locked into an institutional nexus in a way that tended to drain autonomy from the performer community and transfer it to the external mediators and sponsors.”

In one of the great ironies of piping, the publication of important collections of pipe music in the nineteenth century and early twentieth centuries would further erode the freedom of expression in piobaireachd. Judges who were not entirely confident of their ability to judge the best players of the day adhered safely to the collections of Angus Mackay, Donald MacDonald or David Glen, marking competitors down for not playing exactly what was written in the accepted text of the day.

With the advent of the Piobaireachd Society nearly one hundred years ago, says Donaldson, this unfortunate process came to a head, as control of the music was now in the hands of an élite few who not only published the books, but hired the prime instructors and judged the major competitions. They were not accomplished players, but they were powerful. Their positions gave them sway over the greatest names of the day: John MacDougall Gillies, John MacDonald of Inverness and Willie Ross, none of whom could stand up to the power and influence of Archibald Campbell. In complete opposition to what piobaireachd might once have meant to the players, these folk

“…knew little of oral transmission or what it might imply, and failed to appreciate that the simultaneous co-existence of multiple variants [of a tune] might be a normal and healthy condition.”

Now the story becomes riveting, with chapters detailing the history behind the Piobaireachd Society’s first failed series of publications and its influential second series (up to Book 10). The legendary Campbell is painted as a controlling and self-absorbed dictator who claimed to be preserving the interpretations of the master players such as MacDonald, Gillies, and Colin and Sandy Cameron, while in reality amending interpretations and publishing scores mostly to his own liking. Ross, MacDonald, R.U. Brown and others spoke vitriol of Campbell in private, with Bob Nicol providing perhaps the most pithy indictment, told to Donaldson in conversation in 1975:

When Nicol exclaimed, “The book, the book, the bloody book, I can’t do with it at all” he had specific books in mind: namely the Piobaireachd Society Collection (second series) and the Kilberry Collection of Ceol Mor. Of the editor, Archibald Campbell, he declared… “you could be a very clever man, yet no musician.”

Donaldson’s rewriting of the reputation of Archibald Campbell will likely be the most controversial issue in this book, and it will be interesting to see who, if anyone, comes to Kilberry’s rescue. However, Donaldson’s overall argument that piobaireachd as an art form has in the most important ways spiralled downward during the last two centuries is convincingly presented. It has led this reader to reassess not only the performance of piobaireachd in the year 2000, but the process of setting tunes for the major competitions, and indeed our restrictive text-oriented standard of awarding prizes. The argument becomes particularly evident when Donaldson juxtaposes the current stagnant condition of piobaireachd with that of light music, a vibrant, fluid and living musical form, the control of which has remained firmly in the hands of “the performer community.”

(As an aside, Donaldson would most likely approve of the current Piobaireachd Society’s leadership being returned to professional players and its planned release of an edition of the MacArthur manuscript.)

This is a wonderful book, though to get to the meat one must plough through a perplexing initial chapter quite unrelated to piping. Don’t let that put you off.

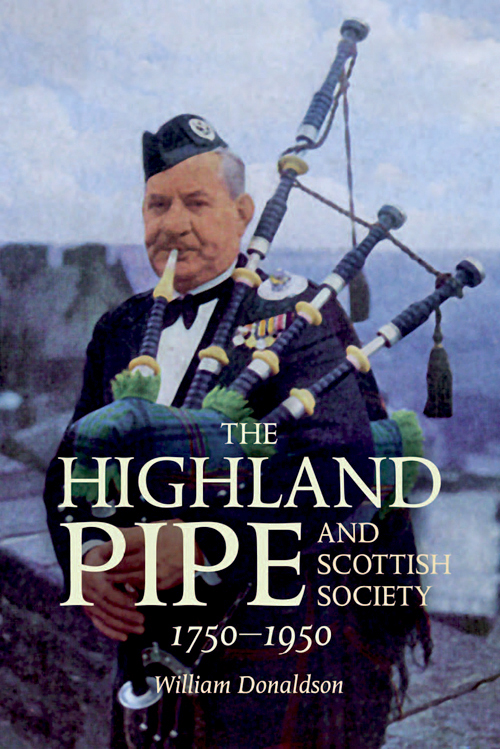

It is also a very expensive book, and considering the nearly $75 price tag one might expect more photos of piping’s great names in addition to the three rarities included: a fabulous 1946 colour cover shot of Willie Ross taken on the ramparts of the Castle, Bob Nicol playing at John MacDonald’s 1953 funeral and a portrait of nineteenth-century icon John Bàn MacKenzie.

If you judge piobaireachd, are involved in its administration, or play it as a serious performer, put this book on your list of must-reads. If the history of piping interests you, pick it up and be fascinated. Otherwise, you might buy it just to say you own a first-edition of what might become one of piping’s more valuable and influential academic works.

Among his numerous competitive achievements, Jim McGillivray has won both Highland Society of London Gold Medals, the Clasp, and the MSR at the Glenfiddich. He is Director of the Piping and Drumming Program at St. Andrew’s College, an independent boys school in Aurora, Ontario.

p|d

What do you think? We always want to hear from our readers, so please use our comment system to provide your thoughts!

Do you have a product that you would like to have considered for review? Be sure to contact pipes|drums. We can’t report what we don’t know about! Please remember to support the businesses that advertise and make the not-for-profit p|d possible.

NO COMMENTS YET