The ensemble judge’s role defined: New Zealand’s Alan Jones argues for drumming knowledge

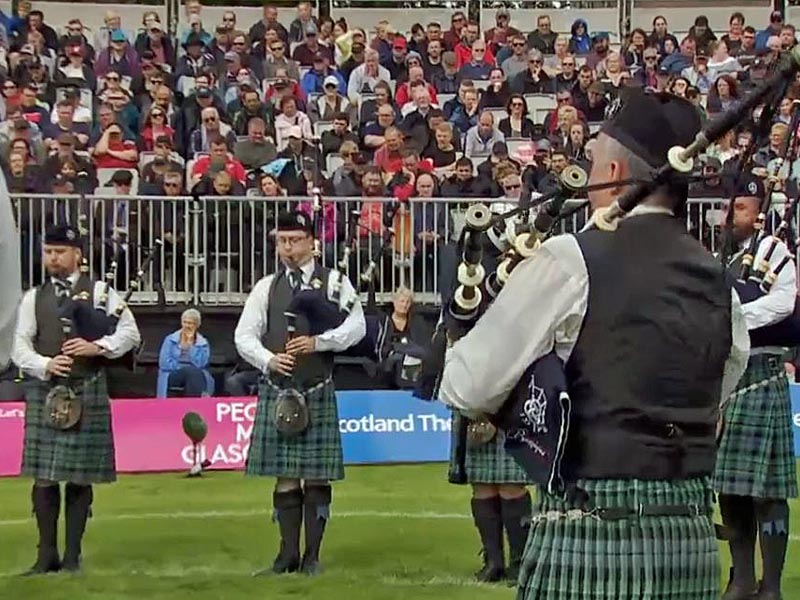

As soon as the Royal Scottish Pipe Band Association introduced in the early 1970s Ensemble as a new category to be judged, there was endless debate about a definition for the role or, perhaps more accurately, the criteria that an Ensemble judge should use to assess a pipe band.

Due to the almost subjective nature of pipe band adjudication, there will be a different answer from every judge, pipe major, lead drummer, piper, and drummer. And if two people agreed on the required judging criteria, the levels of importance they’d apply to each would be different.

Alan Jones of Hamilton, New Zealand, has studied and written about pipe band ensembles for over a decade. His Pipe Band Ensemble website compiles his work in one place. He has shared many of his conclusions with pipes|drums’ readers over the years, and his latest piece strives to define and clarify the Ensemble judge’s role and the qualities he believes are required of the judges themselves.

The ensemble judge’s role defined: New Zealand’s Alan Jones argues for drumming knowledge

By Alan Jones

Who is judging what?

The word ensemble, translated from the French, means “together,” i.e., how “together” are the various sections of the pipe band (pipe section, side section, and bass tenor (soft) section).

In the current pipe band competition format, how clearly defined are the roles of the piping, drumming, and ensemble judges, in terms of measuring togetherness?

Who measures the togetherness within a given section?

Who measures the togetherness between the various sections? Is there any overlap of roles and, if so, why?

Who should judge Ensemble?

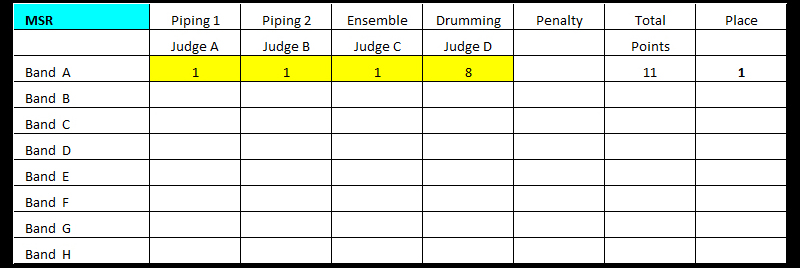

The chart below shows part of a score sheet, taken from a contest that the author attended recently.

Band A is rather unusual in that it has a superior pipe corps for its grade, but with a relatively young and inexperienced drum corps. The drum corps did not play well in this particular event.

The ensemble judge is from a piping background:

In pipe band MSR competition, the pipe corps plays tunes that are, basically, standardized.

This means that a pipe tune’s rhythmic and melodic format is usually “fixed” and seldom open to major changes, particularly in response to any pipe drum ensemble limitations that the tune might have.

Consequently, pipers (in general), are not experienced in listening to the other instruments in the band, understanding the way the music of those instruments function, how they integrate rhythmically, melodically, and sonically, with their own instrument, and acting on that understanding to help bring the various sections of the band more together musically.

If one has little or no experience in writing drum accompaniments, and is therefore unable to follow both the piping and drumming rhythm lines simultaneously during a performance, how can one be qualified to judge ensemble with rigour and objectivity?

Even the very best piping composers seldom consider, or understand, the impact that their tune might have on pipe drum ensemble integration, during the composition process.

Lead-drummers, however, in most cases, do.

Writing a pipe drum accompaniment is not an easy matter. It requires a specialized understanding of the ways in which the pipes and drums come together (rhythmically, melodically, and sonically), and of the ensemble limitations that exist between those instruments. It also takes a significant amount of time to build up the experience to do the job well.

If one has little or no experience in writing drum accompaniments, and is therefore unable to follow both the piping and drumming rhythm lines simultaneously during a performance, how can one be qualified to judge ensemble with rigour and objectivity?

And be able to report on this, using the same pipe drum ensemble “language” that the lead-drummer of the band would understand?

Anything other than this, simply adds another piping judge to the panel, and, as with Band A’s contest results shown above, has the potential to skew the results to favour any band that is stronger in piping.

What should the ensemble judge be listening for?

The author believes that piping, drumming, and ensemble adjudicators have separate roles in judging the musical quality of a pipe band.

There should be no overlap in these roles.

He suggests that in any pipe band competition situation:

- The piping judge should completely ignore the drum section.

- The drumming judge should completely ignore the pipe section.

- The ensemble judge should completely ignore the quality of playing both “within” the pipe section and “within” the drum section.

Below are some examples of the performance elements that an ensemble judge should be listening for. The elements are divided into three sections: Rhythmic, Melodic, and Sonic.

In each instance, the musical background (piping or drumming) with the skill set best suited to judge that element, is given:

P = piping

D = drumming

PD = piping or drumming

Definition of terms used

Melody line (pipes)

- Those core notes in a pipe tune that deliver the basic underlying rhythm. In most cases, embellishment notes are not included in the melody line.

Rhythm line (pipes)

- Those core notes in a pipe tune that deliver the basic underlying rhythm, with all melodic considerations ignored. This might best be explained as the melody line interpreted in monotone. In most cases, embellishment notes are not included in the piping rhythm line.

Rhythm line (drums)

- Those notes in a drum score that deliver the basic underlying rhythm. In most cases, embellishment notes are not included in the drumming rhythm line. It is often useful to be able to follow the drum rhythm line in monovolume (while ignoring all side drum, bass, and tenor dynamics), and/or in monotone (while ignoring all bass tenor section tonal interplay).

Judging Ensemble in the “horizontal”

- Interpreting the degree of rhythmical togetherness between the pipe and drum corps in the monotone, with all melodic, tonal, and dynamic considerations ignored.

Judging Ensemble in the “vertical”

- Interpreting the degree of togetherness between the pipe and drum corps by concentrating solely on melodic, tonal, and dynamic matters.

Rhythmic integration (judging in the horizontal)

This section is judged in the “monotone” and includes all rhythm, tempo, and beat-note integration matters:

- Pipe-drum integration issues at intro (e.g., drum lead rolls finishing ahead of the beat). (PD)

- Drum corps “pushing” tempos (playing slightly ahead of pipe corps). (PD)

- How well the side drum scores integrate with the pipe tunes’ rhythm lines. (D)

- Pipe Drum integration issues at breaks between tunes (rhythm, tempo, and/or beat note discrepancies). (D)

- Pipe Drum integration issues at end (rhythm, tempo, and/or beat note discrepancies). (PD)

- Limitations placed on the drum score writing process by the selected pipe tunes. (D)

Melodic integration (judging in the vertical)

This section judges how well side drum dynamics usage, and multi-pitch bass-tenor playing integrate with the piping melody line:

- How well the side section makes use of dynamics to integrate with the pipe music melody lines. (D)

- How well the side section makes use of off-beat lift to support the pipe music melody line (this will be affected by tune selection). (D)

- How well the bass tenor section makes use of multi-pitch instrumentation to support the pipe music melody lines. (PD)

- How well the bass tenor section makes use of dynamics to support the pipe music melody lines. (D)

Sonic integration

This section judges the balance between the side drum volume, the bass-tenor volume, pitching, and tone, and the pipe corps’s volume, and tone:

- How well the pitch set up and tonal quality of the bass tenor section, compliments the sound set up of the pipe corps. (PD)

- Volume balance between bass tenor section and pipe corps. (PD)

- Volume balance between side section and pipe corps. (PD)

An MSR ensemble judge test

In the author’s view, it is unacceptable to assume that, just because a person has a background in piping or pipe band leadership, they must automatically have the requisite skills to judge ensemble.

An ensemble adjudicator should be able to read “both” bagpipe and side drum music with a high degree of competence.

The author suggests that a minimum requirement for anyone wishing to qualify as an MSR pipe band ensemble judge should be something like:

“The candidate is able to write a simple, ‘rhythmical,’ musically correct, side drum accompaniment to each of any given eight bars of march, strathspey, and reel pipe music (preferably Grade 1 level tunes); be able to defend that composition from a pipe drum ensemble integration perspective; and be able to communicate this defense in a musical language that a lead-drummer would understand.”

The contest judging panel

The author believes that any pipe band contest judging panel, at any level, should comprise:

- Two Piping adjudicators – responsible for determining the quality of the performance within the piping circle.

The piping judge should completely ignore the drum section. - One Drumming adjudicator – responsible for determining the quality of the performance “within” the side drum section, “within” the bass tenor section, and the level of togetherness “between these two sections” only.

The drumming judge should completely ignore the pipe section. - One Ensemble adjudicator – responsible for determining the level of togetherness “between the side drum section and the pipe corps,” and “between the bass tenor (soft) section and the pipe corps,” only.

The ensemble judge should completely ignore the quality of playing both “within” the pipe section and “within” the drum section.

Defining MSR pipe band ensemble

The author believes that pipe band ensemble is best understood, and best evaluated, in three parts:

- Rhythmic Integration

- Melodic Integration

- Sonic Integration

Determining the level of togetherness between the side drum section and the pipe section

Rhythmic integration

The most important yet most complex part of pipe drum MSR ensemble integration is understanding how well the side drum rhythms integrate with the pipe tune rhythm line.

With melodic matters completely ignored in this section, pipe drum rhythmic integration is essentially measured in the “monotone.” The author sometimes refers to this as judging in the “horizontal.”

In determining this level of compatibility, the ensemble judge needs to be able to follow both the piping and drumming monotone rhythm lines simultaneously during a band’s performance.

The assessment includes both tempo and beat note integration elements (esp. at intros, endings, and breaks between tunes).

Influenced largely by the drum score writer’s interpretation of the pipe tune, and his/her commitment to the bands overall ensemble effect, it is also influenced greatly by pipe tune selection, and how well the tune supports the rhythms, rhythm phrasing, and rhythm repetition needs of side drum music.

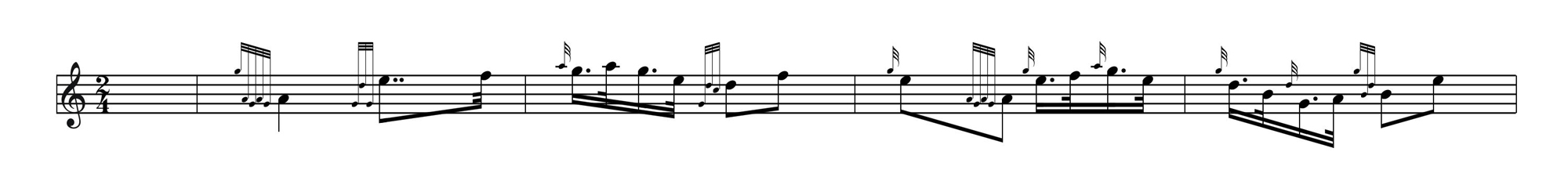

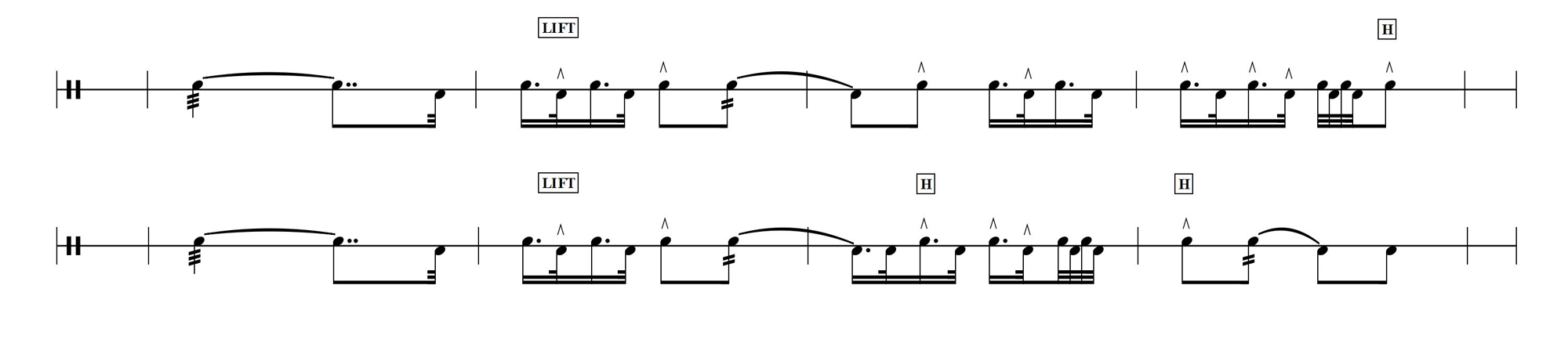

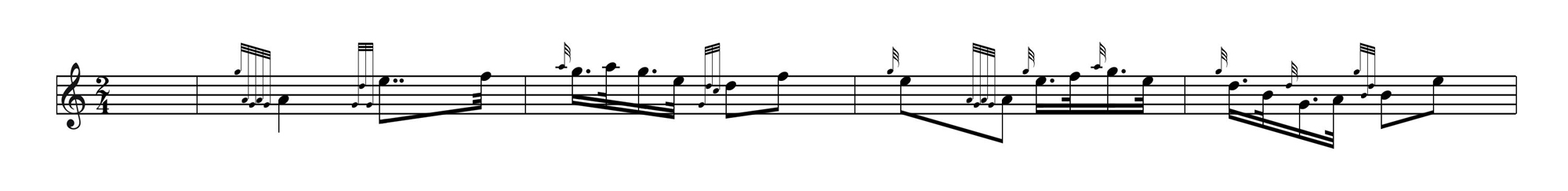

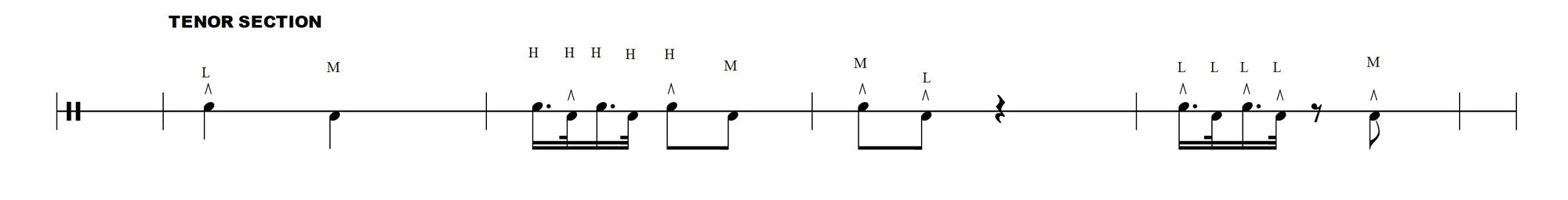

The MSR is largely a dot-and-cut environment. If the side section is integrating well with the pipe section, and the pipe tunes selected are supportive/conducive to good pipe drum rhythmic integration, the band’s overall “dot-and-cut rhythmical effect” should come through very clearly to the listener, for example, the first four bars of the 2/4 march, “Coppermill,” by Michael Grey:

Note the high degree of rhythmic integration between the pipe tune and the drum score.

NB:

The bagpipes and side drum use different methods to add interest to their respective music, and it is inevitable, in a pipe band setting, that there will be some degree of rhythmical separation between the two instruments.

For example, in strathspey music, with its relatively slower tempo, the side drum rhythm set often relies heavily on rudiments based on the triplet group, a note combination rarely found in piping strathspeys.

Recognizing these pipe drum rudiment limitations, and determining how well a given drum corps performance works within these limitations, is probably the greatest challenge for the ensemble judge.

Melodic integration

The author sometimes refers to this as judging in the “vertical.”

Although the side drum is a mono-pitch instrument, it is well capable of integrating with a pipe tune at a melodic level.

This is achieved through the use of dynamics, where different note volumes are used, subtly and selectively, to support the pipe tune melody line, that is:

- Louder drumming notes integrating with “higher pitched” notes in the pipe tune.

- Softer drumming notes integrating with “lower pitched” notes in the pipe tune.

Influenced largely by the drum score writer’s interpretation of the pipe tune, and his/her commitment to the band’s overall ensemble effect, this section can also be influenced greatly by pipe tune selection, and how well the tune supports the dynamic needs of side drum music.

One example of this is within a dot and cut rhythm, when an “off-beat ” side drum accent (cut quaver in reels and strathspeys, or cut semiquaver in marches) coincides with a piping melodic highpoint, resulting in a powerful rhythmical effect that the author describes as off-beat lift, for example:

Note how the drum score makes use of accents to “highlight” some of the pipe tune’s melody line high points.

Sonic integration

Sonic integration, from an “ensemble” standpoint, is the degree to which the side drum section’s pitch and tone complement the sound produced by the pipe corps.

The competition side drum is a mono-pitch instrument.

This means that once tuned, its pitch is “set” and unlikely to change during performance.

Tuned under very high tension, the side drum produces a sound so high that it is classed as being of indefinite pitch, meaning its pitch cannot be accurately determined.

How does one, therefore, report on the tone and quality of tone of such a highly pitched instrument? Even when the drums sound “flat” or the snares haven’t been set up well?

When evaluating music played at such a high pitch, at what point is that sound no longer complementary to that of the pipe section, and how does one prove that?

Determining the level of togetherness between the bass-tenor section and the pipe section

Rhythmic integration

The most complex part of pipe drum MSR ensemble integration is the understanding of how well the piping and drumming rhythms integrate.

The rhythms delivered by the bass/tenor section should be closely integrated with the side drum score, which in turn, should be closely integrated with the pipe tune.

They should all complement each other.

When they do come together accurately, it is very noticeable.

This is influenced by the drum score writer’s interpretation of the pipe tune, and his/her commitment to the band’s overall ensemble effect.

It is also influenced greatly by pipe tune selection, and how well the tune supports the rhythms, rhythm phrasing, and rhythm repetition needs of side drum music.

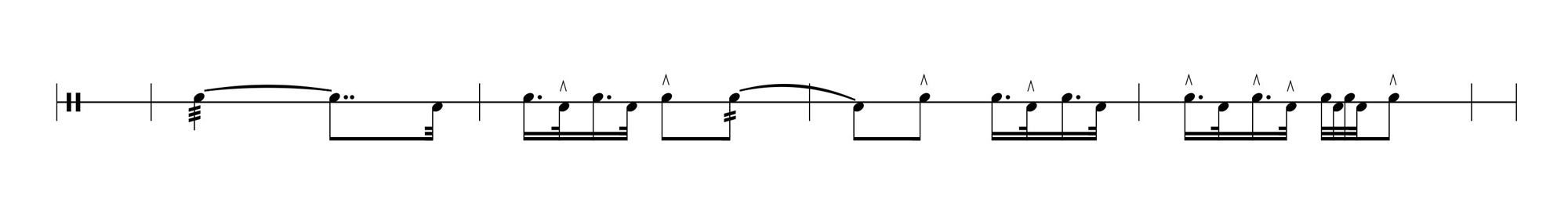

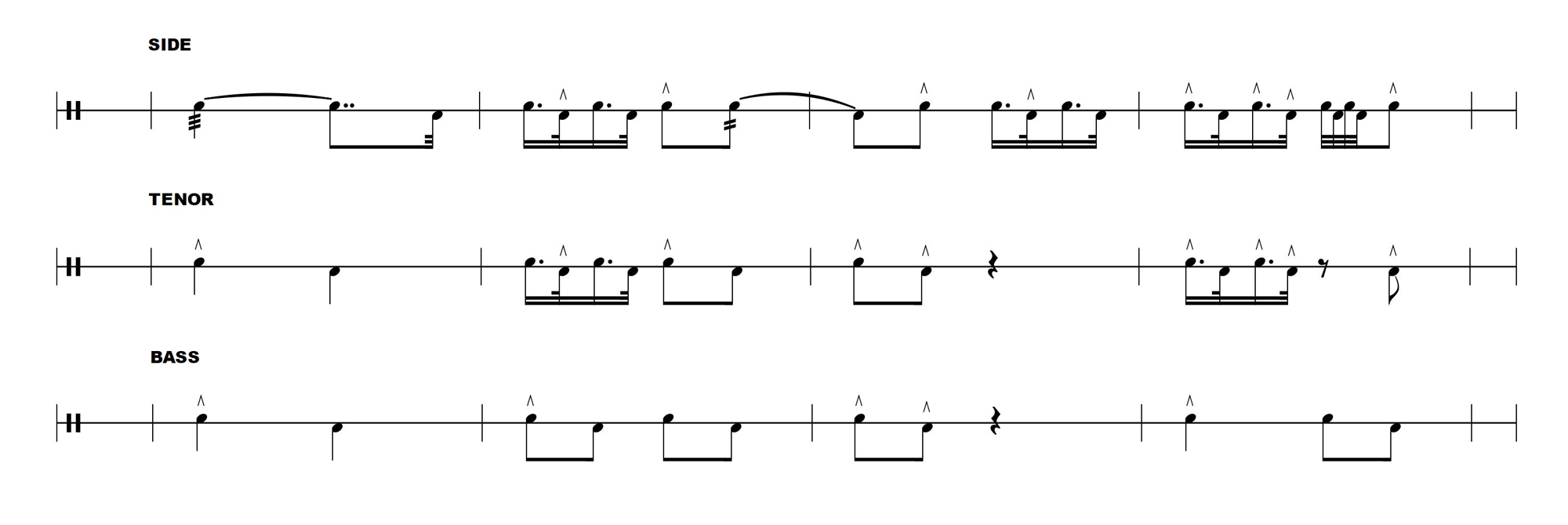

For example:

Note the high degree of rhythmic integration between the pipe tune and the side, tenor, and bass scores.

Sonic integration

Sonic integration, from an “ensemble” standpoint, is the degree to which the soft section’s pitches and tones integrate with and complement the sound produced by the pipe section.

Let’s look at the bass and tenor drums separately.

The bass drum

The bass is a multi-volume instrument.

It is also a mono pitch instrument, meaning that once tuned, its pitch is “set” and unlikely to change very much during performance. The bass is usually tuned to produce a pitch and tone that is complementary to that of the pipe section.

The instrument itself, its dimensions, the drum heads used, how they are fitted, the dampening (damping) system used, the type of drumsticks (mallets) used, the way in which the mallets are applied to the drum head, and the way in which the instrument is carried while playing, all contribute to the quality of the tone produced, as does the way the instrument is played.

The bass drum’s ability to “project” its sound needs to be included here too. Maximizing the efficiency of the instrument includes things like limiting the number of points of contact with the drum shell (allowing it to vibrate); using a drum dial to ensure that both drum heads are set at equal tension and resonating “together” while producing the desired pitch*; and using a dampening (damping) system that removes any overtones that occur along the outer circumference of the drum head, while limiting the number of points of contact with that head (allowing it to vibrate).

The degree to which a well-set-up, well-played bass drum can integrate with and complement the overall ensemble sound of a pipe band should never be underestimated.

* It is perfectly possible to produce the desired bass drum pitch with both heads set at completely different tensions.

The tenor drum

The tenor drum is (usually) a mono-pitch, multi-volume instrument.

The tenor section often comprises several drums set at different individual pitches.

They are usually tuned to produce pitches and tones that are complementary to those of the pipe section.

The instrument itself, the drum heads used, how they are fitted, the dampening (damping) system used, the type of drumsticks used, the way in which the sticks are applied to the drum head, and the way in which the instrument is carried while playing, all contribute to the quality of the tone produced, as does the way the instrument is actually played.

The tenor drum’s ability to “project” its sound needs to be included here, too. Maximizing the efficiency of the instrument includes things like limiting the number of points of contact with the drum shell (allowing it to vibrate); using a drum dial to ensure that both drum heads are set at equal tension and resonating “together” while producing the desired pitch*; and using a dampening (damping) system that removes any overtones that occur along the outer circumference of the drum head, while limiting the number of points of contact with that head (allowing it to vibrate).

The degree to which a well-set-up, well-played tenor section can integrate with, and be complementary to, the overall ensemble sound of a pipe band should never be underestimated.

* It is perfectly possible to produce the desired tenor drum pitch with both heads set at completely different tensions.

Melodic integration

The bass tenor section is more than capable of integrating with the pipe tune melody.

This is achieved by tuning the various instruments so that they complement the pitch and tones produced by the pipe section.

The accurate set up and tuning of the “soft section” requires considerable expertise, with quality of outcomes varying greatly in the pipe band world.

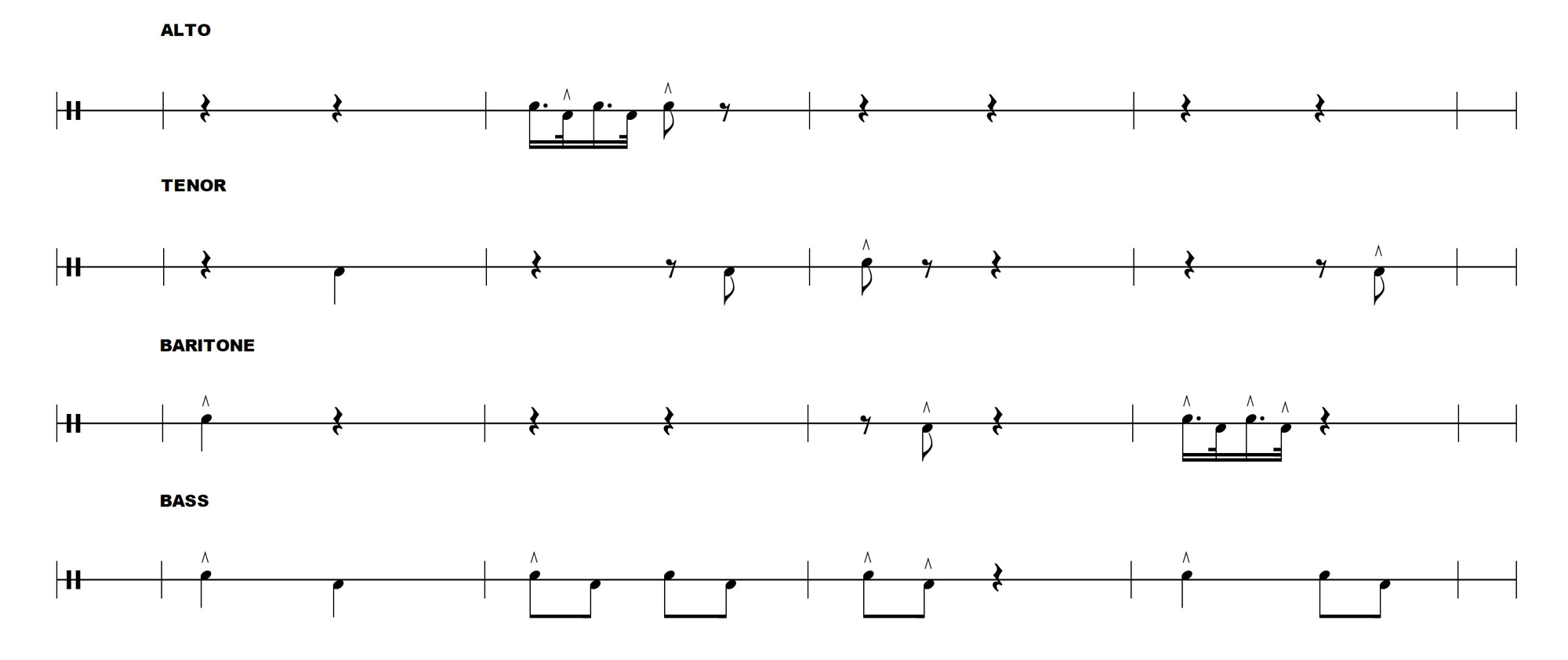

In the higher grades, the soft section typically comprises one bass, and three or more “tenor” drums (set at different pitches). For the purposes of this writing, the author will use the following drum combination:

- 1 x bass

- 1 x alto

- 1 x tenor

- 1 x baritone

Bass drum

Usually tuned to the bass drone of the pipe corps.

The bass drummer generally plays variations of the underlying S-W-W-W rhythmic metre, but also integrates more closely with the rest of the drum corps during moments of high rhythmic interest.

Alto drum

Tuned to the upper range of the bagpipes.

The alto drummer is usually responsible for integrating with the important higher-pitched notes and rhythms in the pipe tune melody. The soft section’s flourishing arrangement gives the alto drummer “space” to achieve this.

Tenor drum

Tuned to the mid-range of the bagpipes.

The tenor drummer is usually responsible for integrating with those important middle pitch notes and rhythms in the pipe tune melody. The soft section’s flourishing arrangement gives the tenor drummer “space” to achieve this.

Baritone drum

Tuned to the lower range of the bagpipes.

The baritone drummer is usually responsible for integrating with those important lower pitch notes and rhythms in the pipe tune melody. The soft section’s flourishing arrangement gives the baritone drummer “space” to achieve this.

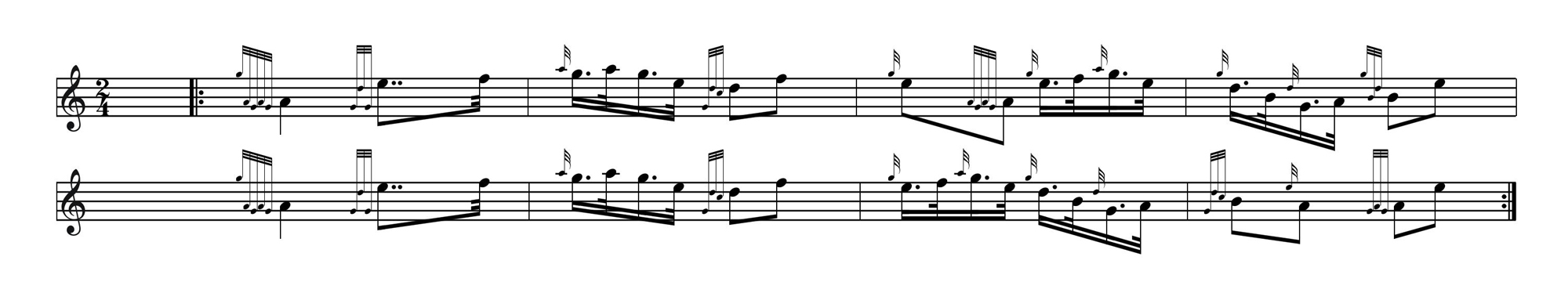

For example:

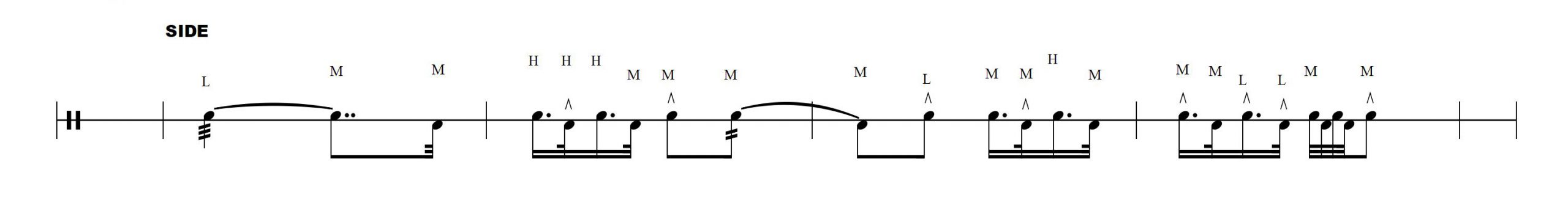

Here, most of the note positions in the side drum rhythm line, have been designated high (alto), medium (tenor), or low (baritone), based on their corresponding note positions in the pipe tune melody line.

This information then determines how the bass tenor score might interact “tonally” with the pipe tune via the side drum score.

The information can then be used to create individual alto, tenor, baritone, and bass scores:

Some minor shifting of pitch responsibilities between the different instruments may be necessary to smooth out the overall effect. The flourishing routine is then designed to integrate closely with these scores.

Bass tenor side sound projection limitations

The bass, tenor, and side drums all have their own sound projection strengths and weaknesses, and the ensemble judge needs to be aware of these.

Bass

A well-tuned bass drum is able to project its sound many tens of metres beyond the MSR contest circle, but its projection field includes both sweet spot and dead spot areas.

A judge standing side on to the bass is likely to be hearing the instrument at its best. Still, when listening from directly in front, or behind (from the bass drummer’s perspective), the quality of sound can be completely different.

Drumming and ensemble judges should be aware that it is unfair to appraise the quality of sound of the bass drum when listening to it from a dead spot position.

That is why some bass drummers “crab walk” as the band marches from point A into the circle, so that the drumming judge (usually standing behind the side drum section at this point in the performance) is receiving the best sweet-spot sound possible.

Bass drums with larger dimensions can produce a “bigger” sound (richer and with more volume) with less effort from the player and project that sound further out from the band than is usual.

The author believes that, for a similar given area of projection field, a well-set-up larger bass drum will have a greater proportion of sweet spot coverage than would a more conventionally sized instrument.

Drumming and ensemble judges should be aware that it is unfair to appraise the quality of sound of the bass drum when listening to it from a dead spot position.

Tenor

These days, because of advances in technology, a well-tuned tenor drum is able to produce a better quality of sound, is able to be heard more clearly, and is able to project that sound far further, than in former times.

However, it is the author’s opinion that by carrying the drum in a harness and playing it in an upright position, a lot of that sound can be lost into the ground.

By carrying the drum in a sling, or altering the harness to carry the drum at a slight angle to the ground, more sound off the bottom of the drum can be projected outwards to where it can be heard.

Players should be mindful, however, that carrying a drum in a sling usually brings the instrument’s shell into contact with the body of the player, reducing its ability to vibrate. This is also true when using a leg rest. Some modern harnesses allow the drum to be carried without this type of contact, allowing the instrument to operate more efficiently.

Some experimentation may be needed to find a ‘system” that produces the best sound projection outcome.

Side

As with the tenor drum, the author is an advocate for carrying the side drum at a slight angle to the ground, allowing for more of the sound off the bottom of the instrument to be heard.

There is a big difference between listening to a side drum section from behind, and listening to it from the front.

So often the author sees drumming judges adjudicating from the rear of the band only, and not taking the time to walk around to listen to the side drums off their top heads.

In the author’s view, it is relatively easy to tune a set of side drums to sound good “off the bottom”; it is a totally different story to be able to tune a set of side drums to sound good “off the top!”

Timbre

The author defines timbre, in a pipe band sonic integration context, as being any sound that remains unique to a given instrument, once the matters of volume, pitch, and tone have been addressed, following the tuning of the pipe, side, or tenor (soft) section.

Usually, an instrument’s unique sound results from a combination of: its design, the materials that it is made of, and how the characteristics of these materials might have changed over time.

Thus, an instrument’s timbre, most often, can be attributed to its manufacturer, its model, and its age; and why it is common practice for pipe bands to purchase new chanters and drums in matched sets.

For example:

Two visually similar tenor drums are set up equally using identical drum heads and dampening (damping) systems. Yet, after tuning them to deliver the same pitch, volume, and tonal quality, they still produce a different sound.

This is likely to be a timbre matter (something unique to the instrument itself).

In most well-set-up bands, great efforts are made to reduce the impact of any timbre differences between the instruments to the point where they are indiscernible to the listener.

Alan Jones began learning pipe band snare drumming at 12 with Manawatu Scottish in Palmerston North, New Zealand. By his early twenties, he had achieved a national solo drumming title, two national pipe band drumming titles (as a corps drummer), and had travelled to Scotland for a year to play a full competition season in Grade 1. Upon returning home to New Zealand, Alan and his wife (whom he met in Glasgow) settled in Hamilton, where he was to become the lead-drummer of the local Grade 2 band, a position he held for many years. As a teacher of mathematics and gifted and talented children for most of his working life, Alan has always had a great interest in working with young people, with much time invested and success achieved over the years through various drum-teaching initiatives. Although now retired from bands, he still assists locally as a learner-drumming tutor or score-writer, when required. He owns and operates Pipe Band Ensemble.com.

We hope subscribers have enjoyed Alan Jones’s interesting and scientific approach to discovering what might be more conducive to a more effective ensemble and more fullsome ensemble judging.

NO COMMENTS YET