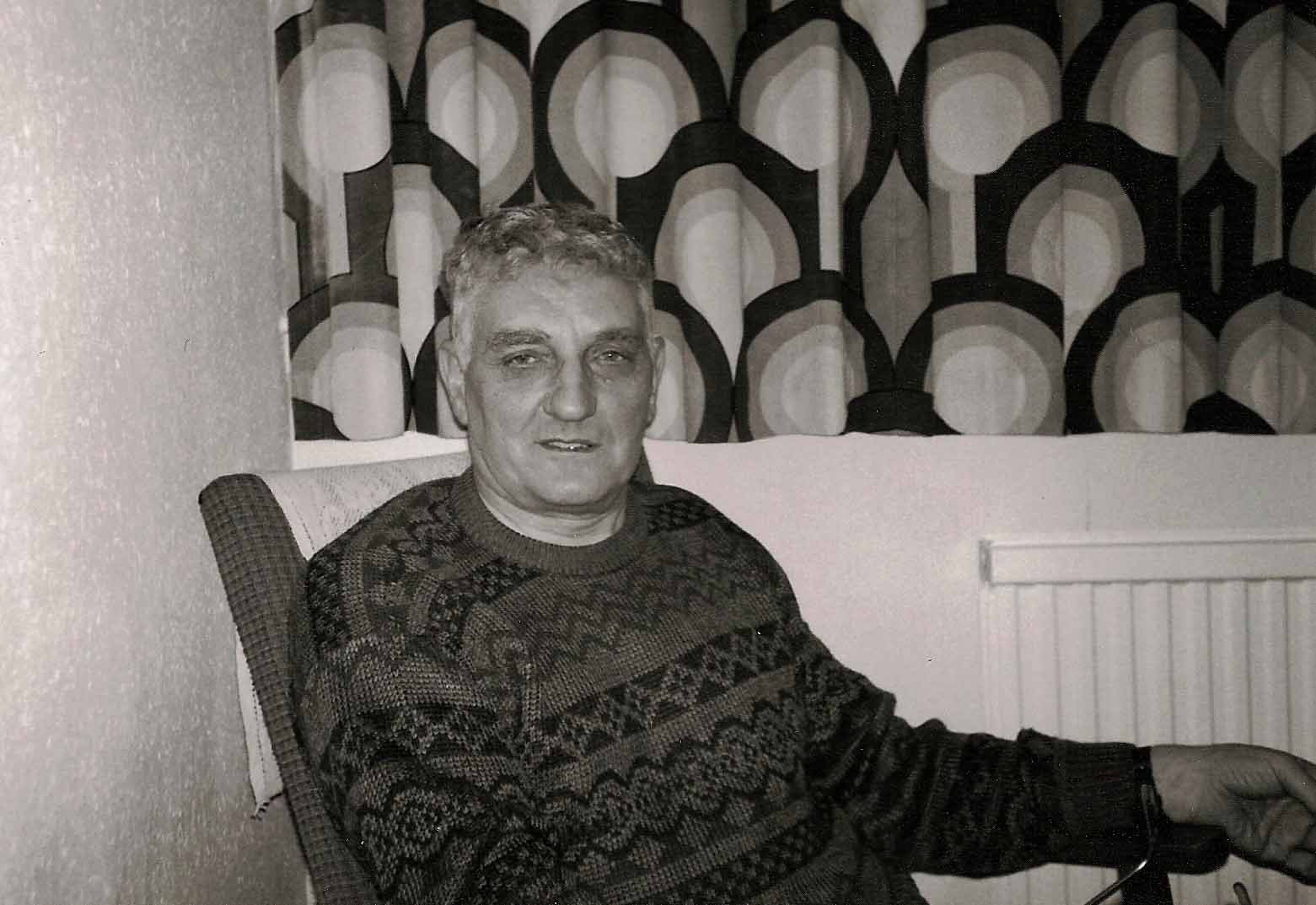

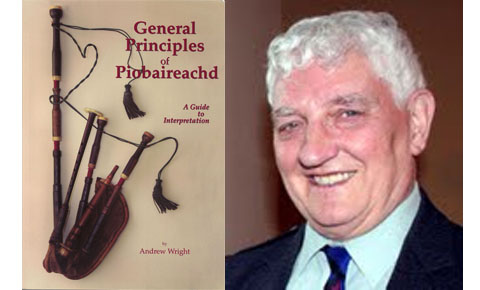

Andrew Wright: the 1995 pipes|drums Interview – Part 1

When Andrew Wright died on October 23, 2022, the piping and drumming world lost a remarkable figure. He left behind a legacy of piobaireachd tuition, whose excellence that will carry on as long as the big music is played.

In the winter of 1994, we got together with Wright at his home in Dunblane, Scotland, for an exclusive pipes|drums Interview. The interview with him was our second, following a shorter one in 1987. In 1995, the piping and drumming world had undergone substantial change, and Andrew Wright was in the middle of a lot of it.

In the nearly two decades since, technical standards have increased, most top bands have become substantially larger and younger, and many top-level solo pipers are competing into their fifties and sixties. In 1995, Andrew Wright was still competing at age 59, something of an anomaly then. He was still striving to win the elusive Clasp at the Northern Meeting, which had eluded him since winning both Highland Society of London Gold Medals in 1970. He was a regular prize-winner in the event, but he never did capture the prize.

Interestingly, in 1995 no other piper in the 25 years since Wright had turned the rare “Double” of winning both Gold Medals in the same year. Since then, though, John Cairns (1999), Douglas Murray (2014), and Ian K. MacDonald (2016) have accomplished the feat.

But in re-reading the interview, we notice how much has not changed. We still struggle to reconcile the future of our music, our competitions, and very viability of what competing pipers and drummers are accustomed to doing.

Here’s Part 1 of the 1995 pipes|drums Interview, including the original introduction. (A reminder that this interview is copyright of pipes|drums and cannot be used without our expressed, written permission.)

It was 1987 when we first sat down with Andrew Wright for a very brief interview. The piping world changed a lot over those eight years, and Andrew Wright has been involved in some of the most significant of those changes.

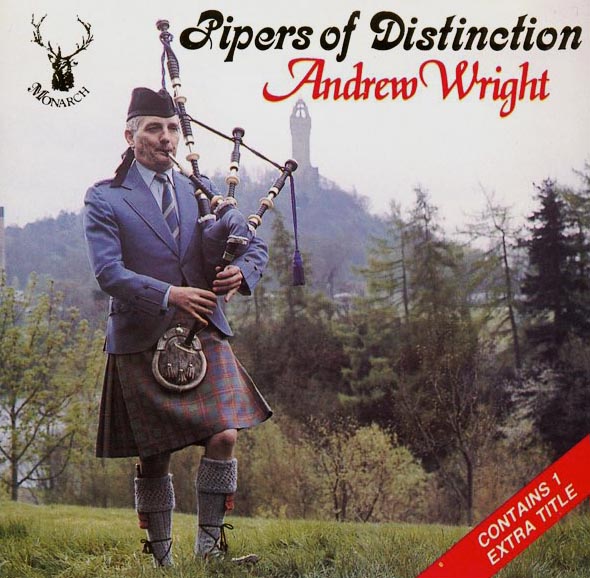

When most people think of Andrew Wright, the word piobaireachd immediately comes to mind. He has devoted much of his piping life to the study, teaching, and playing of ceol mor, and today he is considered to be one of the foremost authorities on the subject. For nearly twenty years he studied with Pipe-Major Donald Macleod, one of John MacDonald of Inverness’s prized pupils, and one of the most formidable competitors, composers and tutors the piping world has seen in the last hundred years.

Andrew Wright had additional tuition in the greater music of the great Highland bagpipe from Bob Brown and Bob Nicol, who added further insight and polish to his approach and playing of piobaireachd. Perhaps the most important contribution these men gave to him was their unreserved style of teaching, of freely passing along their knowledge of piobaireachd. Wright learned something equally as precious as the music itself from these masters – he learned how to teach.

And teach he does, His patient and enlightened approach to the music is quickly absorbed by his students, many of whom have gone on to win major prizes on the piobaireachd platforms around the world. He teaches with an open mind, freely encouraging sound musical interpretation. To him, strict adherence to a particular style is antithetical to good music, and he is always exploring new settings of old tunes,

His competition record is sterling. In 1970 he won the rare “Double,” by capturing both Highland Society of London Gold Medals, a feat that has not been achieved since. His list of ceol mor competition successes is prodigious: the Open at Oban, the Bratach Gorm (three times), the Open at London (four times) the Uist & Barra (three times), as well as almost every other piobaireachd award offered in the UK.

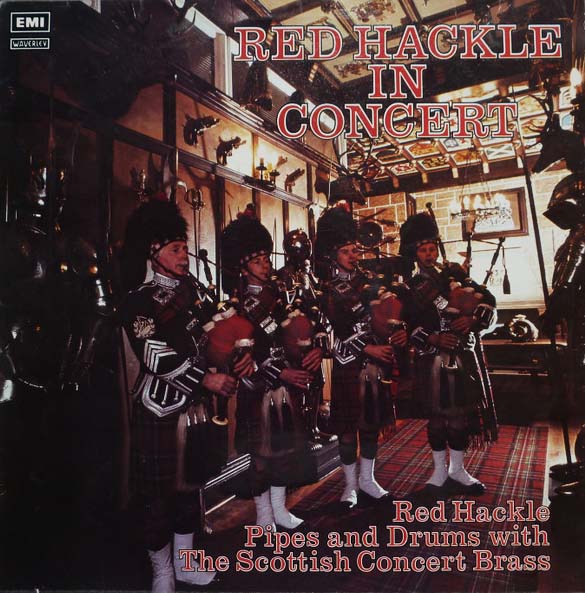

But even though Andrew Wright’s foremost attribute might be piobaireachd, he has a significant background in pipe bands. While playing the solo circuit during the late 1960s and ’70s, he managed also to play with the famed Red Hackle Pipe Band under legendary Pipe-Major John Weatherston. At the time, it was an infrequent occurrence that a soloist in Scotland-particularly a soloist with such a devotion to piobaireachd-would manage to enjoy the pipe band world. Competitions in Scotland are generally divided between the Highland Games, where there are only solo piping, athletic events, and Highland dancing, and pipe band contests, where the RSPBA manages the day’s machinelike production of bands competing for prizes. Unlike the North American structure, few events in Scotland offer both band and solo events, and therefore to do both requires tremendous dedication and flexibility, not to mention adroit time management skills.

Andrew Wright is still very much a part of the pipe band scene as a member of the RSPBA’s adjudicators’ panel. He is known as a judge who calls it like he hears it, politics or track record be damned, and puts particular emphasis on a band’s musical performance, instead of the all-too-common tack taken where best tone equals most merit.

Two years ago he became President of the Competing Pipers Association at a time when the group was in disarray. The previous season had seen the scene torn apart by a disastrous players’ boycott of the major events, with the aim of pressuring competition committees into accepting the conditions of the Association of Piping Adjudicators. During the “Boycott Year,” Andrew Wright was one of only a handful of Scottish pipers who refused to join the boycott, and willfully supported the major contests.

When he became President of the CPA, he immediately tried to repair the fractured solo piping scene, by forming a new joint committee with the Piobaireachd Society, the competition committees, the players, and the APA. It is Wright’s hope that compromise can be reached with all four organizations so that everyone can just get on with the music and get away from the politics.

For all his political acumen, Andrew Wright’s demeanour is quiet. He is an intent listener, able to hear and weigh all sides of an issue, and then make a decision. His political approach appears to be much like his piobaireachd approach: always consider the sensible options and keep an open mind.

Andrew Wright lives in Dunblane, a small town a few miles north of Stirling, in a comfortable house with his wife, Isabel, and children. By profession he is a plant manager at a large woolen mill in the nearby town of Alloa. Over the last winter, we met with Andrew Wright for this interview.

pipes|drums: What initially attracted you to take up the Highland bagpipe?

Andrew Wright: Most young boys in industrial Glasgow during the 1950s ended up in one of the youth organizations, the Boys Brigade or the Boy Scouts, and it was inevitable that I would do likewise. It was in the 213th Glasgow Company of the Boys Brigade that I was given the opportunity to learn the bagpipe. There had been no pipers in my family up until that time, and somehow I ended up being a piper, it might just as easily have been the bugle or the drums.

p|d: Your career really has been a rare

mix for a piper: numerous years with a top Grade One band-Red Hackle; both Gold Medals and almost every other award in piobaireachd; an esteemed position on the RSPBA judging panel; President of the Competing Pipers Association; Gold Medal winning pupils; pupil of Donald MacLeod, pupil of Peter MacLeod, pupil of Bob Brown and Bob Nicol; the list goes on, How have you ever been able to juggle everything so well?

AW: A lot of these things happened at different times over a span of years, but I’ve always enjoyed being involved with other aspects of piping over and above the playing side. I was fortunate to obtain a great deal of excellent tuition, and it was inevitable that I teach to put something back into it. I was a pipe band player for a number of years before I started to compete in the Open competitions. In those days competitions were not graded and anyone trying his hand had to go in against the top players right away. Many didn’t last the pace and gave it up before hitting the prize lists. Over the years one thing has led to another. In the case of the Competing Pipers, however, it was because there was a job that had to be done.

p|d: You mention the Scottish system, where there’s not much of a solo ladder for amateurs to climb. You’re thrown in with the famous soloists if you want to compete after the age of 18. In your case you would have been thrown into the ring with guys like Hector and John MacFadyen, John Burgess, and so on.

AW: The top men at that time certainly were Hector MacFadyen, John MacFadyen, Ronnie Lawrie, and John Burgess. It took me four or five years until I won the piobaireachd at Aboyne.

p|d: That’s a good prize; Aboyne is where you have to submit twelve tunes.

AW: Yes, I remember being pleased.

p|d: Do you think that the Scottish system is a good one?

AW: It exists at the Highland games, but most of the indoor competitions, and certainly the major competitions, are graded now, which means a younger player can go in at an appropriate level, and find his feet there.

p|d: When you were with Red Hackle playing with a band and doing the solo piping circuit was a relatively uncommon thing. Were you ever criticized for playing light music in a “bandy” style?

AW: That’s hard to answer, as most of my time and interest was really on piobaireachd. The band never affected my light music.

p|d: Do you think a solo piper’s playing is hindered by a band?

AW: Provided that the player has the time available to commit him or herself on these two fronts, I think it makes little difference to the technical standard. It amid make a difference to one’s perception of the music especially nowadays with the great influence of the modem style of drumming. In a pipe band you can become a follower rather than a leader. In a good band it’s quite easy to switch to automatic pilot and just be carried along by the pipers on either side of you. When you play solo you have to lead.

p|d: Do you think that solo piping has become more regimented, with fewer unique styles, as a result of more soloists today playing in bands?

AW: Yes, I think solo piping is more regimented than what it was. Looking back at the very good light music players of 20 years ago they all played a little bit different, some of them would play fast, some of them would play slow, others would play pointed but nowadays everybody tends to go down the same track and that could be due to what is successful in competition.

p|d: What about looking at it the other way around? Is a pipe band helped by having good soloists involved?

AW: Without a doubt. The quality of the individual has a great influence on the quality of the group. Back in the 1960s for example, it was possible for a good pipe major to blend a group of local players and win a major championship. There are many instances of this having happened when much of the technical work was cut out of the tunes in order to obtain the blend. With a very high standard of technical ability in pipe bands and the rise in standard nowadays this would not be possible. If we take today’s prize-winning Grade One bands, virtually every player will be more or less note perfect and able to sustain a quality instrument through that performance.

p|d: When you’re judging, can you tell the difference between a top band who has a top soloist as a pipe major and a band that doesn’t? I’m thinking here of guys like Terry Lee, Ian Duncan, lain MacLellan, and Bill Livingstone.

AW: Most pipe-majors of the top bands are top players in their own right.

p|d: I guess I’m talking about the difference between a band led by a very good player, and one led by a top soloist who can understand and develop the subtleties in, say, strathspeys.

AW: If you take the Edinburgh City Police under Iain McLeod, they had a special touch to them that to me only came from Iain McLeod’s own perception of the music. A lot of bands today with soloists as pipe-majors are drum-dominated.

p|d: In your opinion who is, or who was, the greatest player you ever heard?

AW: This is a difficult question because I’ve heard so many brilliant players over the years who on their day would be unbeatable. My yardstick would have to be for the most complete piper over the full range of the music, and I would say that would be Pipe-Major Donald MacLeod. He was complete in virtually every respect and had total command over the full repertoire. His technique was perfect, his playing musical and rhythmical without having that over-rehearsed element that is apparent in many players. His playing to me-especially in light music-always gave the impression of being spontaneous and fresh.

Another of his attributes was to play and hold the attention of a non-piping audience. I witnessed this a couple of times during recitals he gave in the Edinburgh Festival when he had a non-piping audience completely quiet when he played “The Desperate Battle of the Birds.” To me that is one sign of a good player: the ability to play for a non-piping audience and grab their attention.

Other pipers have made a lasting impression on me. The march playing of James MacGregor and Captain John MacLellan often springs to mind, and a live broadcast in the late 1960s by R.U. Brown when he played “The Old Woman’s Lullaby” and “Lament for Mary MacLeod.” Of course the list is endless, and I could go on and on. As I said, it is a very difficult question.

p|d: You were the last one to win both the Oban and Inverness Gold Medals in the same year. Why do you think no one has been able to turn the trick since you did it in 1970? Is it a matter of good luck?

AW: Good fortune plays a part and the winning of any competition depends on many factors. For example, the order of play in a big entry, the tunes chosen by the judges on the day, who the judges are, how the bagpipe goes on the day. I’m of the opinion that in nearly any top competition if there were two benches of judges they would each come up with a different result. Of course practice and preparation and a degree of professionalism are other important factors in winning prizes. I have no doubt that all of these points will come together for some other player before long.

p|d: You did your mandatory National Service with the Royal Scots for two years, and you gained something from that, no doubt. What are some of your stand-out piping experiences with the Royal Scots?

AW: After my three month initial training I was posted to the Pipes & Drums 1st Battalion, stationed at the time in Berlin. There were a lot of ceremonies and parades. I served under two pipe-majors: the first one was Pipe-Major George Fraser, an ex-Seaforth, and latterly under Pipe-Major R.S. Burns, a very good composer who wrote the hornpipe, “Newmarket House,” and was an excellent player. Whether the military did my playing a great deal of good, I don’t know. It certainly helped me with my knowledge of reeds. It wasn’t really until I came out of the forces and finished studies that I started to get down to piping seriously, and that coincided with Donald MacLeod coming to Glasgow.

p|d: Let’s tum to something a little more current-the Competing Pipers Association and the Association of Piping Adjudicators. You became President of the CPA at a time when the organization was in turmoil, when it was virtually split be tween pro-APA and anti-APA factions. What’s your goal now with the CPA?

AW: “Pro-APA” and “anti-APA” is perhaps not the right way to put it. There was never any objection to the APA in the CPA. The objection was to the CPA boycott of the major competitions, and my immediate goal was to eliminate the idea of the boycott from the members of the CPA. This goal has been achieved and the next step is to establish the recently set up joint committee for judging. The reaction to this at the present time by competition promoters and those on the judging list has been extremely positive.

p|d: What do you think the APA must do to be a more effective and useful organization?

AW: That can only be for them to decide, but I think that their constitution must be examined, especially the part that restricts them to judging only with their own members. This rule would be acceptable if a large majority of the available judges were members of the APA, but their membership comprises only a minority of the available judges. Their present stated position is that they are here and available if anybody wants their services and I think we should respect their stance and let things be as they are.

p|d: You were one of the very few top soloists-in Scotland, anyway-to take a stand against the boycott of 1993 and play in the major events. The next year you became President of the CPA. Do you think anything at all was accomplished by the boycott?

AW: The purpose of the boycott was never made exactly clear to the CPA membership. The majority of those who boycotted believed that it was because the APA members were not being asked to judge. This is a fallacy. The APA mem bers could have been judging at the major competitions both in 1993 and 1994. The point was they insisted on sitting on benches comprised solely of their own membership.

Competition organizers were and are not prepared to accept that as a condition of acceptance to judge. In the case of the Northern Meeting, competitions have taken place there since 1841 and these were preceded by the competitions at Falkirk that began in I781. We’re talking about tradition and heritage and I, for one, was not about to sabotage this in order to suit a small group of adjudicators, however much I respected all of them as individuals. Other pipers felt much the same and so the competitions went on, but with reduced entries in 1993.

Of course 1994 saw everything back to normal. The boycott, however, had one positive result, although almost as a by-product, and that was the proposal and setting up of the joint committee for judging. That proposal was geared to bring the APA back into the fold, but unfortunately they have refused to come. It is important that the function and the make-up of this joint committee is fully understood. It comprises members from the CPA, the Piobaireachd Society and representatives from major competition promoters. The purpose is to maintain and monitor a list of judges from those avail able. The list will be regularly reviewed and complaints dealt with. It is now up and running, and it is a watchdog committee and chaired by the President of the CPA, whomever that may be in the future. The reaction of all those people involved has been extremely positive, including judges whose results have had to be questioned. I think this a huge step forward for piping and it will be my job to entrench the joint committee.

p|d: So the APA has at least raised awareness that there might be a problem with judging.

AW: Right. I think that there was a problem, there always has been a problem, and there always will be a problem. We can never have every competition judge be perfect, but we’ve now got a mechanism whereby judges are accountable.

p|d: Do you think that would have come about without the APA? Did it necessarily take a boycott to get that far?

AW: It was never asked for before the boycott started. The boycott was purely to get the APA judging and as I said, the joint committee is virtually a by-product of the boycott. There was no problem with the competition organizers in getting them to accept the joint committee.

p|d: When you stop competing, do you see yourself getting involved more with solo judging on a regular basis?

AW: It would be the natural progression, but at this moment in time I have no urge to get involved in the judging of solo competitions especially at a professional level. I do the odd bit at the moment on amateurs or juveniles and I enjoy that but I have no desire just now to get involved in the judging of senior competitions. One reason for that would be that I would use different parameters than what other judges might use.

p|d: Parameters? What do you mean?

AW: I might be less inclined to take note of a small choke or something. I’d be more inclined to take note of a poor interpretation of a tune, or a piper who was ad-libbing and feeling his way through it. I like to hear pipers who know exactly what they’re doing whether I agree with it or not, you can always tell if the player knows exactly what he’s doing. It doesn’t necessarily have to be the same as I do, but you can tell right away. What doesn’t appeal to me are players who are in perfect control of the instrument, with perfect fingers, but are not putting anything into the tune. I would lean very heavily toward the amount of musical thought.

p|d: Would you prefer to be on a bench of two or three?

AW: I would much rather judge on my own, but be judged by three, which means I want my own way all the time.

p|d: Why would you want to judge on your own?

AW: Because I could take complete responsibility for the result.

p|d: Have you ever had trouble separating politics from the art? Is there a danger that groups like the CPA, the APA, the Piobaireachd Society, the RSPBA, obscure the musical objectives pipers should put first?

AW: These groups have their own function within piping and within each of the groups there is no doubt differences of opinion on how things should be done. This is part of a democratic process. I have never had any problem in my involvement with any of these groups in keeping the music separate. In fact, I would say that the reverse could be the case.

p|d: What do you mean?

AW: I’ve found the end product of all these people to be the music, and when I say music I mean competition. Unfortunately today, bagpipe music means competition.

p|d: Do you think getting so wrapped up in rules and regulations obscures playing itself?

AW: Piping is so big nowadays that there have to be rules. Before the RSPBA was set up, and even back in the early days of the major solo competitions, things were a bit haphazard. Piping is big business now. Young men will gear their whole career towards being a top piper, and will travel the world to become a top piper.

p|d: Mostly the ones outside of Scotland.

AW: That’s right, so it’s very serious business isn’t it?

p|d: Pipe bands: what do you like most about the top pipe bands today?

AW: What is immediately apparent in top bands today is the integration between the pipes and drums –the ensemble effect. This is a highly elusive quality; it’s either there at the start or it isn’t. It’s immediately obvious when the band starts to play. And it’s not confined solely to the top bands in Grade 1. Some lower grade bands achieve this where some of the top grade bands do not. I think it emanates from the drum corps and the degree of awareness shown by the leading drummer to what’s happening in the pipe section.

Another facet affecting this is that the pipe tuning in the top bands is down to a fine art, being able to sustain chanter tuning with full drone back up throughout a complete performance.

The common trend is to open a selection with a hornpipe, and frantically march toward the circle. This sets the pace for what follows, perhaps with the view that the more notes that can be played, the more clever the performance is. This will change in due course.

p|d: You’ve talked about some of the best things. What do you think some of the worst qualities are of today’s top bands?

AW: I’ve always taken the view that an audience is there to listen to what the performer wants to play. The choice of material is entirely up to those who do the playing. It’s then up to the listener to like it or not. Having said that, I question some of the material which bands are using at the present time in competition. The common trend is to open a selection with a hornpipe, and frantically march toward the circle. This sets the pace for what follows, perhaps with the view that the more notes that can be played, the more clever the performance is. This will change in due course.

p|d: When you’re judging, what are the qualities you look for in a pipe band performance?

AW: Usually if a band starts off good, it stays good; if a band starts bad, it doesn’t improve. Usually with the opening parts, after the intro, you can tell if the performance is going to be in the top quarter or the bottom quarter-barring a severe mishap, of course. I have always been on the piping side, and I base my assessment on what is good piping. I lean toward the musical rather than the purely technical. Many bands play perfectly without producing good music. Often the pipe section in these bands is completely dominated by the drummers. In other words, they follow the drummers rather than the other way about. Ensemble also has an effect as good ensemble normally ties in with good piping. Sound is always very important. I like a full drone effect and this is only achieved by having every drone in the band and every set of pipes operating and in tune. I do not like incomplete instruments, as often this is nothing more than taking the easy way out, and many bands do take this option.

p|d: It seems that these days the band with the best tone generally wins the contest no matter what they play. The RSPBA rules state that a judge isn’t allowed to comment on a setting or particular style of how a tune is played. Do you think judges should be able to comment on the type of tune, the selection itself, the musical interpretation?

AW: I think all the judges must take the musical interpretation into consideration. I certainly do.

p|d: But, strictly speaking, the RSPBA rules suggest that if a band came out playing Robert Reid’s setting of “Abercairney Highlanders,” and you couldn’t stand that, you say this is rubbish and you put them last for that alone, you’re really breaking their rules.

AW: What I don’t like is if some band’s playing a classic tune, and the pipe major introduces a second part of his own competition. I come down very heavily on that although I wouldn’t specify it. I’ve heard one band play a new second time to “Mrs. MacPherson of Inveran,” and theoretically I’m not allowed to subtract points, but I’ll write them off.

p|d: What about judging medleys? In general there seems to be a lot of talk about the medley these_ days, how it’s out of control as a competition format. Do you think it should be in a judge’s parameter to come down hard on a band for the content of their selection?

AW: I’ve done that often on point sheets and I certainly take that into consideration.

I think that if a judge has any musical taste he must be encouraged to [critique content]. That’s the beauty of pipe band judging: you can state what you like about it or what you don’t like and you can lay yourself on the line and stand or fall by your own decisions.

p|d: You’ve actually said that on a scoresheet?

AW: Sure.

p|d: Do you think judges should be encouraged to do that?

AW: I think that if a judge has any musical taste he must be encouraged to do that. That’s the beauty of pipe band judging: you can state what you like about it or what you don’t like and you can lay yourself on the line and stand or fall by your own decisions.

p|d: Let’s talk about Red Hackle. That band came close a number of times to winning the World’s, but the title was never John Weatherston’s with that band. Do you think Red Hackle should have won the World’s?

AW: We were second three times at the World Championships, and the band was certainly good enough to have won the title. At Perth in 1968 three bands actually tied for first place and the result was decided by ensemble preference. Red Hackle ended up third. That one was very disappointing as in those early days of ensemble judging, Red Hackle, probably more than any band at that time, tried to create an ensemble effect. The leading drummer, Wilson Young, was very innovative. One comment on the drum point sheet always sticks in my mind from that era and it said, “Has the bass drummer gone wild?” Without a doubt Red Hackle was a musical rather than a technical band, and John Weatherston, who won the World Championship with the 277 Light Regiment, said that the Red Hackle were a far superior band in every respect.

p|d: Some of today’s younger pipers haven’t even heard of Red Hackle. Can you give them some insights on the band?

AW: The Red Hackle was formed following the end of the World War II. It was started by a group of Black Watch ex-servicemen in the Govan area of Glasgow. The Red Hackle was the emblem of the regiment. Red Hackle was also a well-known brand of whisky marketed by Hepburn & Ross in Glasgow. The owner of the firm was an ex-Black Watch officer named Charles A. Hepburn. Sponsorship followed sometime in the early 1950s, and the band’s name was changed to Red Hackle Pipes & Drums. It was probably the first sponsored pipe band, and the sponsorship was quite lucrative, even by today’s standards. The band came to the fore in the mid-1950s under Angus Macleod, and won many championships, but got only second in the World Championships to the Edinburgh Police under Donald Shaw Ramsay by a quarter of a point.

I joined the band as a very young boy, and it was then I first came into contact with Donald MacLean of Oban, who played for a couple of seasons. He was a small man with large hands and he held his fingers well over the chanter just passed the first knuckle joint and they did not come high up off the chanter. He had an amazing repertoire of tunes, especially traditional reels, jigs and hornpipes. He was a pupil of John MacColl, and he played marches in a very slow, round, open, yet musical style. I remember him winning the marches at the Pitlochry games playing “Dugald MacColl’s Farewell to France,” a tune not much favoured by solo piper nowadays. I had assumed from hearing him play, that the great march composer MacColl must have played in the same style, but I later heard it said that MacLean played more like MacColl than MacColl played like himself, which meant of course that MacLean exaggerated MacColl’s style.

Other players in the band round about that time were Norman Gillies and Iain MacFadyen. In the early 1960s the playing of the band went into decline and it wasn’t until John Weatherston took charge of the band around 1965 or ’66 that things started moving again. He had already won a World Championship with the 277 Light Regiment of the Argyll & Sutherland Highlanders and his influence was immediately felt.

For the next decade, the band was a major force at all the competitions and gained the Champion of Champions award in 1972. The band at that time had a pleasing, sweet sound and played Hardie chanters with what in those days was a high pitch. The style of play in the band was slowish and pointed. It was a style attached to the Pipe-Major, but he made a musical statement at all times. The band was also very innovative in its day, being one of the first to do albums with other instruments, and also popularizing pieces like “The Intercontinental Gathering” and “The Cockney Jocks,” which was composed by Malcolm MacKenzie, who took over when John Weatherston retired. Under him they came fifth and third in the World’s, but shortly after that the Red Hackle whisky firm was sold to Aberlour Glenlivet and 1he band was renamed Clan Campbell in order to promote a new brand. Not long afterwards, within a few years, the sponsorship was withdrawn and the band broke up. It’s now part of pipe band folklore like some of its contemporaries such as Clan MacRae Society and Muirhead & Sons.

p|d: You talked before about the music that John Weatherston developed and the ensemble affect. Was there any feeling at the time that the band wasn’t being fairly recognized for some of the musical things, that you were hard done?

AW: The band had its share of success. All pipe bands think they’re hard done unless they win.

p|d: But, was it a situation where you were playing some different things and you might not have been understood. I mean you get comments like “has the bass drummer gone mad?”

AW: That one was a wee bit hard to take because it was in the type of selection that was musical rather than technical-nothing like what the bands play today. Wilson Young and John Weatherston introduced “Skye Boat Song” halfway through the selection and Wilson Young got the bass and tenor drums to represent a thunderstorm and the thunder of waves, or crescendo, and come back down again with the side drums cutting out and that’s when that comment came out from an old, traditional drumming judge.

p|d: You are kind of known as a judge who calls it like you hear it, sometimes coming out with a quite different result from your fellow judges. What is your approach to band judging?

AW: Pipe band judging is becoming increasingly more difficult, the pressure on a judge, especially in the first grade of a major championship and especially the World’s is tremendous. Point summaries are issued after the competition with each band and with each band allocated points in order of merit over sometimes thirty performances. With the amount of retrospective statistical analysis that takes place the judge becomes the judged. The pipe band judges monitoring group, while being a positive step to ensure fair judging, could also inadvertently lead to judges playing safe. The odd man is subject to the most scrutiny, when in fact he could be the one who is correct.

Over the course of a few seasons, there is no doubt who the top bands are, but they do not always tum it on every time they play. Apart from obvious things such as tone and intonation, I base my assessment on three things: the first being what the band plays, two being how the band plays, and thirdly the way that a band plays-their musical interpretation, how they handle timing. I lean heavily towards the last of these options. I wouldn’t give a band first purely on the basis of having a better tone than one of its competitors as long as the tone was sweet, well-tuned and it’s sustained, I would lean toward the way the tunes are played.

The bands are always bitching. We can’t have ex-members of bands judging that band, or we can’t get ex-pipe-majors of bands judging the band they led. The fact is that competent and knowledgeable judges are required to be around the band scene for a great number of years. Competent but unknown judges just do not exist; they are not available.

p|d: What do you think about chanter and reedmakers and other purveyors of products-should they be allowed to judge important pipe band events?

AW: This has always been a bone of contention. Bands prepare diligently and travelling distances to compete at major championships. For overseas bands a great expense is involved, and when the band does not get a result, it is only natural that they look for a reason other than the obvious and rightful one that is, that they never played well enough on the day or their performance level is below that which is required for a prize. I have been in bands, and I have been around bands and I know what attitudes are. The last thing a band will do is take a good hard look at themselves. Equipment suppliers who judge are the obvious crutch to support this disappointment and apart from chanter and reed suppliers, I have heard criticism of other equipment suppliers, new uniforms, new drums and various other consumables.

I’ve also heard that argument applied to when Canadian judges judge Canadian bands at the World’s. The bands are always bitching. We can’t have ex-members of bands judging that band, or we can’t get ex-pipe-majors of bands judging the band they led. The fact is that competent and knowledgeable judges are required to be around the band scene for a great number of years. Competent but unknown judges just do not exist; they are not available. A competent judge can only become so by having been around the scene for a long time. It’s all a matter of integrity and something which should be addressed by the judges monitoring group and the music board when new judges are being appointed.

p|d: But if you take a look at any other judged event, whether it’s highland dancing or ice skating or fencing or whatever, they will never, ever allow even the shadow of conflict of interest to obscure the final result. They eliminate it before it’s a factor. With pipe bands a lot of money rides on this stuff. A lot of money can be made off of a World Champion band playing a particular make of chanters. Can we ever eliminate the element of bias before the contest, or are we too small?

AW: If bias exists, I think it would be very difficult because, if pipe band judges were available in Timbuktu, I don’t have any doubt that such neutral people would be asked to judge. The top pipe band judges have been steeped in the pipe band playing all of their days. We could have what we have or we could get complete strangers in to judge that knew nothing about it.

p|d: Sure, but what about judges whose livelihood depends on the bands that they judge?

AW: There is no doubt that the present system is open to abuse, but the Judges Monitoring Group must tackle this.

Stay tuned for Part 2 of the 1995 pipes|drums Interview with Andrew Wright in the next short while.

NO COMMENTS YET