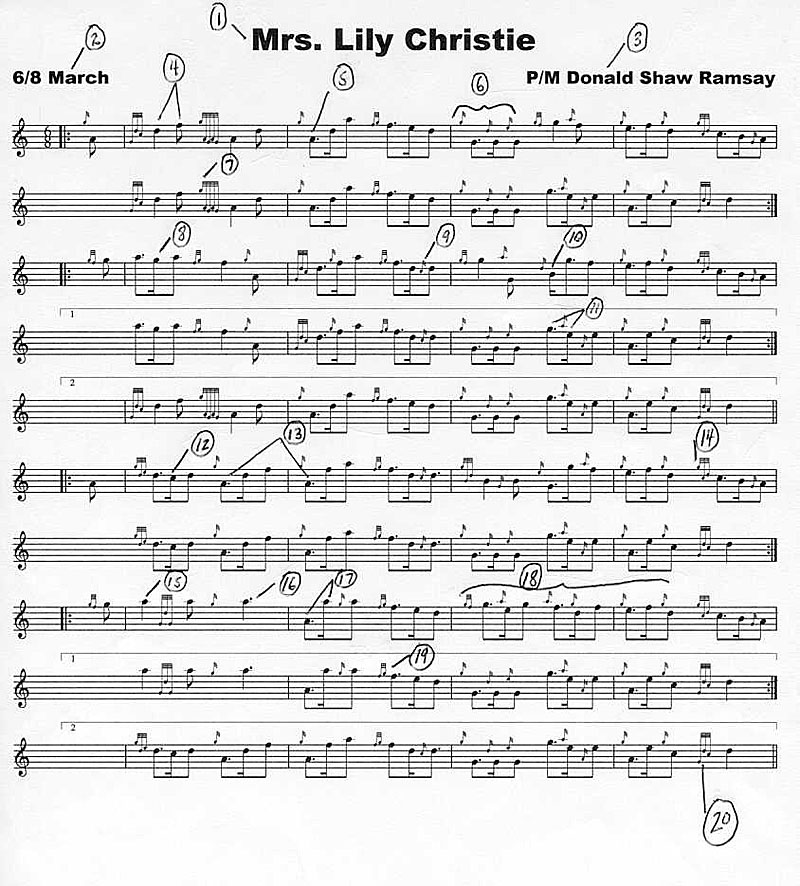

From the archives: What’s in a Tune? An annotation of the great 6/8 march ‘Mrs. Lily Christie’

Jim McGillivray’s terrific annotation of the now classic 6/8 march by the late Donald Shaw Ramsay, this feature was originally published in the February 2003 print edition of pipes|drums. Just open the graphic and match McGillivray’s commentary with the numbered areas on the manuscript.

1. Published in Donald Shaw Ramsay’s second Edcath book around 1955, this tune was made immensely popular in Ontario in the mid-1970s by the Clan MacFarlane Pipe Band under Ken Eller. Soon everyone was playing it until no one could stand it any more and out it went. It is currently being rediscovered.

2. Described by David Murray as “the marching music of the British army,” 6/8s are the tunes that got soldiers across deserts during wars. Their expression is not complex, but requires strong, consistent pointing and controlled, driving forward-motion. A band tempo might be 84-90 bpm, a good solo tempo 80-84.

3. Ramsay was at the centre of the pipe band scene in the 1950s and ’60s. He led the Edinburgh City Police to the World Championship in 1954 and the Invergordon Distillery band of piping superstars to a seminal pipe band recording. Among his other compositions are “Angus MacKinnon,” “Schiehallion,” “Jimmy Young,” and “Tam Bain’s Lum.”

4. Resist the temptation to round these two notes out. Quarter notes in 6/8 marches need to be stretched to the utmost.

5. Dotted eighth notes are important too. Consistent pointing of these notes generates the ‘swing’ in the 6/8 march. Make the dotted note very long and the following sixteenth very short, and do this consistently throughout the tune.

6. The ubiquitous G-D-E appears pointed in some tunes, round in others. In this one it is pointed. The trick is to point the first note without then cramming the D and E gracenotes together.

7. Birls in particular can be very rhythmical movements, especially in 6/8 time. Be sure the G gracenote is squarely on the beat (the finger hits the chanter when the foot hits the floor) and give the movement a tight but audible three-pulsed ba-ba-da

8. This high G is a sixteenth note, not a gracenote. Don’t turn it into a high A hit. Enunciate it and remove the E finger when you play it.

9. In the last 20 years most D hits have become full strikes to low-G. They don’t have to be. This one sounds better as a lighter hit to C, just as written. Be discriminating.

10. Hitting short notes on the beat is a challenge. Be sure this short B is squarely on the left foot. Resist the temptation to put the following high G on the beat. Stretching the high G quarter note that starts the bar will help.

If you do these sorts of things with doublings you play the whole tune ahead of the beat. Nobody will tap their feet to your tunes; they’ll think about dinner.

11. This is tricky. Resist when tempted to rush off the high G in order to leave time for the high A gracenote and the E strike. Hold the high G; make the E before the strike audible.

12. Like the short high G in bar one of part two, this short C often gets turned into a hit. But it is a big, black note. Hold the dotted D before it, but let the C be heard.

13. This run of three note grouping with the same pointing illustrates the need to play consistent expression in 6/8 marches. All three dotted eighth notes need to be held. Neglect one and the spell of the music is broken.

14. As with all doublings, put the G gracenote on the beat, not the D gracenote. The G finger hits the chanter precisely when the foot hits the floor. This is a widespread problem and it bends tunes out of shape. Relentless practice chanter work gets it right.

15. Hold all quarter notes, but hold this one until the cows come home to bring out the power of the grip.

16. Here’s a quarter note with a dot on it – the longest note in any 6/8. Sit on this high A until the last possible nanosecond. Drop to the low A with a great thump and hold it. It’s a powerful rhythmic technique.

17. Hold the low A here, but don’t turn the two high A’s into a doubling. Articulate the first one.

18. This is a demanding phrase, requiring finesse and accuracy. A good musician slows it down to a crawl, places crisp gracenotes accurately, holds the dotted eighths and enunciates the sixteenths without losing or gaining tempo. Mediocre musicians say, “That didn’t sound right; oh well, I’ll move on.”

19. The half-doubling F behaves just like doublings: the first note in the movement is on the beat. In other words, your F and high A fingers hit the chanter at the same time as your foot hits the floor. Don’t hit the F early and then play the G gracenote on the beat. If you do these sorts of things with doublings you play the whole tune ahead of the beat. Nobody will tap their feet to your tunes; they’ll think about dinner.

20. The D throw comes in open and closed varieties. North Americans generally play the closed movement while U.K.-trained players tend toward the open movement. The open throw sounds lovely in some slow airs and marches. Experiment. You don’t have to play what you were taught or what everybody else plays.

To hear an MP3 of Jim McGillivray playing this tune on practice chanter, go to: PipeTunes.ca – “Mrs. Lily Christie”

NO COMMENTS YET