Is piping and drumming a welcome place for Black players? – Part 2

The publication of Part 1 of our feature story resulted in exactly what we hoped for: healthy and constructive dialogue.

Is piping and drumming a welcome place for Black players? – Part 1

Is piping and drumming a welcome place for Black players? – Part 1

There are still many in the piping and drumming world who don’t like it when difficult questions are asked about sensitive topics. They will often have a knee-jerk reaction, defensively in high dudgeon that their reputation is somehow being impugned.

Nothing to see here. Move along. Sweep that difficult issue under the rug. Shut up and play.

We can understand that perspective. Who wants difficult questions interrupting what is supposed to be a benign hobby?

pipes|drums since its inception has taken a different tack. Only by asking questions and seeking answers can we gain the information we need to form opinions, to make our avocation even better.

How can we have the temerity to ask such a question like “Is piping and drumming a welcome place for Black players?”

We’ve seen the same reaction over our 30-odd years of reporting on piping and drumming every time we’ve asked questions and brought forward important issues for discussion.

We’ll keep doing it.

We hope that everyone reads the insights we gathered for this particular piece. It’s important reading. No one’s character is being attacked. Like all pieces that deal with hard topics, we’re gathering details and trying to learn.

The economist John Maynard Keynes famously said, “When my information changes, I change my mind. What do you do?”

We are not necessarily here to change your mind but, if from the information you gain you become more enlightened, we will have provided our most important service.

Let’s begin Part 2 by asking the hardest question:

Is there systemic racism in piping and drumming?

By definition, when something is “systemic,” it is fundamental to a predominant social, economic, or political practice. If racism is systemic in a social culture like piping and drumming, it might be so ordinary that it goes unnoticed. It’s just the way things are.

If you happen to be a newcomer and on the receiving end of systemic racism, you could be hyper-attuned to problems that need to be corrected.

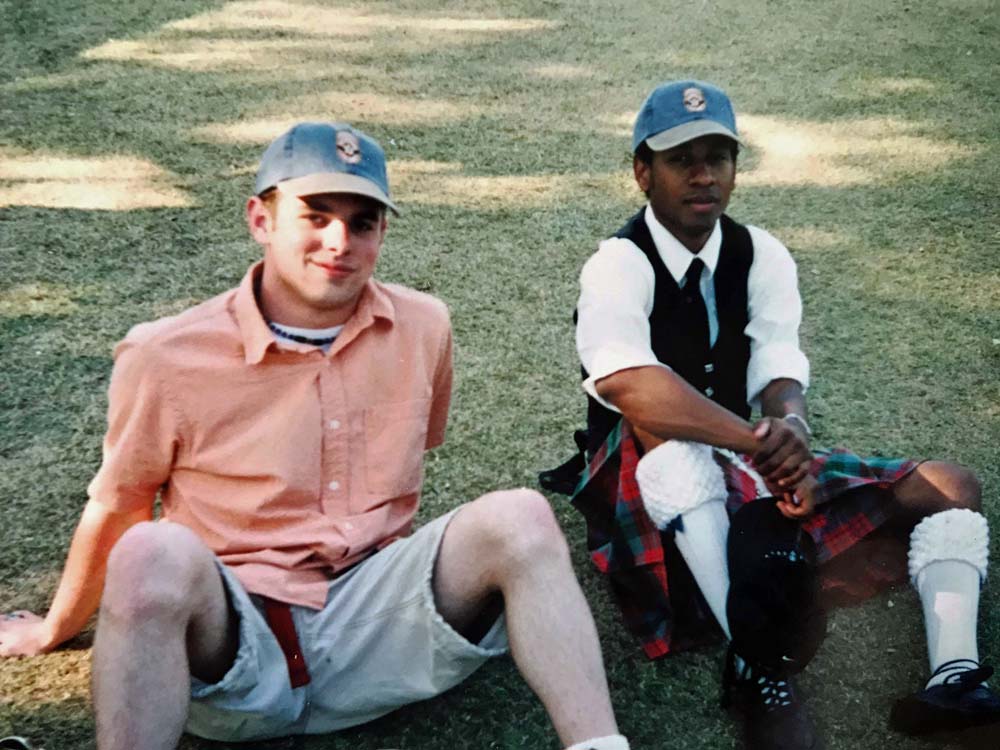

“I do believe there’s systemic racism in the pipe band community,” Art Peters says when the question is posed to him. “When I first started, all I saw were white males and very few females. I think generations are taught how to do things, and they just continue as normal. I also recognize that not a lot of people of colour back then participated in this music.”

If systemic racial problems persist, players of colour are more likely to leave than put up with blatant or subconscious transgressions designed to segregate, whether intentional or not.

In piping and drumming, those willing to fight for what’s right are in the minority. Rocking the boat just isn’t in the DNA of the majority of players in an art form couched in competition that is subject to the biases and perceptions of judges, administrators and even stewards who have the power to override any performance with a stroke of the pen.

“I hope things have changed,” Kolton Stewart says, “but certainly, my experiences in several bands left me feeling welcome by some and excluded or ridiculed by others. Looks, words, sub-groups that left me out of the loop made me feel something was wrong. Certainly, if it was not race, which I feel some were discriminating against me, my age definitely was part of systemic discrimination, and it created an oppressive environment for me. I believe because the pipe band world is such a long historical tradition when anyone comes into that world that doesn’t fully fit that mould, they can face some systematic discrimination.”

And, so, most of us tend to go along with whatever just is. Even when we see the need for change, we’re all too often loathe to advocate for it, for fear of corrupt reprisal.

What can we do?

“White privilege” – the benefits that white people inherently experience over non-white people, mainly if they are otherwise under the same social, political, or economic circumstances – is just as present in piping and drumming as in any culture or group.

No one is particularly at fault for the white privilege that exists in piping and drumming. Until the 1960s or even ’70s, civilian piping and drumming was a place mainly for the working-class. You didn’t necessarily need to have money to participate.

All that changed with international travel, more expensive gear, and a general decline in local “community” nurturing the arts. One still might find initial lessons for free from the local band. Yet, after the first six months or so, a new player will be faced with having to purchase expensive gear and pay for travel and accommodation to competition locations.

To be sure, the problem is not exclusive to piping and drumming. It exists everywhere where white people own most of the wealth and the power that comes with it.

Those with money are those who can afford the price of participation.

“I believe white privilege is very real,” Sutherland says, “but, paradoxically, much harder for people like me to fully see and understand than for people of colour. What I would say to those who deny it exists is this: by the mere fact that I happened to be born into a family with a history of piping and pipe bands, I was given a huge advantage in my piping career over nearly everyone else. That’s very easy for me to see. If you look at the world’s top pipers, you’re fairly hard-pressed to find one who isn’t a second-, third-, or even fourth-generation piper. That’s no fluke. It’s an admittedly crude, but hopefully not offensive, analogy but it demonstrates what I think we all understand implicitly: we’re often more a product of our privileged opportunities than true organic talent, and it’s hard for those who have only ever seen opportunities materialize in front of them to picture what life might be like without them.”

“Pipe bands have policies that state there can be no discrimination, but there are so many sub-groups and hierarchy that things become difficult to address,” Kolton Stewart says. “Pipe-majors and those who run the bands need not to become a part of the oppression, sub-group gossip and exclusion. Leading by example and including all people would help create a welcoming culture, and the word would get out that things are improving.”

Art Peters agrees that we all need to act differently and check ourselves as we encourage all to learn, regardless of gender, sexual orientation, race, religion or age.

“I believe that having bands step out of their comfort zone to recruit and gain exposure will attract more persons of colour,” Peters says. “Why limit your thinking to what’s only around you? I’ve met some amazing musicians in the pipe band world, whose musical knowledge should be shared with others.”

It often starts with one person who’s bold or courageous enough to say No to inequity and Yes to fair play. We see it regularly in piping and drumming. Participants are reluctant to criticize deeply entrenched norms because they fear bullying retribution and turn a blind eye to apparent problems.

So, the problems persist, and all of us who remain willfully tolerant of blatant or subversive corruption, bias and racism are part of the problem.

There are heroes of positive change, though, and their praises are usually unsung.

“I owe everything to Kevin Blandford,” Peters says. “He was a pioneer to me because he broke all the norms. We had members who were Black, Latino, Asian, gay, straight, male and female. Kevin didn’t care what you looked like. He just wanted to teach us and produce good music.”

“Tyler Fry, Brian Fry, Craig Colquhoun, and Kincardine drumming legend Norm Dunsmore and many others were the people who always stood up for me and made me feel like I belonged,” Kolton Stewart says. “If I were feeling shy and unwanted, they would always just say ‘get in there’ and put me in the circle. Through Tyler, I met Jim Kilpatrick, who gave me a private drumming lesson, and he treated me like I was a normal everyday drummer despite being the age of four. It’s these types of people who I always will be eternally grateful for who made me have a positive outlook of my experiences in the pipe band world.”

“If the only places we go to recruit and entice potential pipers and drummers of colour to join bands are traditional Highland games, we’re doomed.” – John Sutherland

When most pipe bands are desperate for players, one might assume that the time is ripe for proactive change, to welcome and attract all those interested in learning our arts. Although Black persons might see mainly – or even only – white males playing the instruments they might like to learn, bands and associations can reach out to all communities to tell them there’s a place for them here.

“I don’t think I have a definitive answer to How do we expand representation in the pipe band community?” Sutherland says. “However, if the only places we go to recruit and entice potential pipers and drummers of colour to join bands are traditional Highland games, we’re doomed. Especially – and I hate to throw any Highland games under the bus here – if your event takes place in front of a Confederate monument. Yikes.”

Mandla Ndabula feels that outwardly proactive encouragement and even recruitment of interested Black learners is not necessary.

“The community in its existence should act as a draw without having to actively target and recruit people of colour,” Ndabula contends. “The pipe band community exists in a bubble. There are few spheres in a social space where one would encounter bands: emergency services, military, and schools. While there are a fair number of social brands, what then matters are the spaces and circles in which the bands move.”

So, perhaps it’s up to us pipers and drummers to go past our comfort zone of Highland games and closed circle social groups to become a part of broader and more diverse communities.

“Piping and pipe bands, besides being historically majority white and male, tend to hold on to traditions and romanticize the past when, in reality, piping and pipe bands are better now than they’ve ever been in history precisely because we’ve moved forward and questioned past doctrine and traditions – and included women!” John Sutherland continues. “Why should we gate-keep and hold on to old traditions, like playing in a circle with our literal and figurative backs to the audience, when what would benefit piping most is eschewing the old ways of the past to truly legitimize our musical art form? If we want to see ourselves and be seen as artists – true musicians, even – rather than just a cultural stereotype, we need to do a better job of appealing to those who do not look like the picture that most people have in their heads when they imagine a piper.”

“Who wouldn’t be interested if someone like Reid Maxwell or Steven McWhirter just popped up and started playing – who wouldn’t be interested in something like that?” – Owen Russell

We can see other art forms that were once all-white, all-privileged, and we can see diversity. None of them are perfect, but they’ve been able to change their make-up and complexion far more. So why not piping and drumming?

“We may be missing the joy of experiencing the Yo Yo Ma or Jimi Hendrix of bagpiping during our lifetimes simply because they don’t look like G.S. McLennan and feel that they wouldn’t belong,” Sutherland argues. “Those of us with privilege need to do a better job of working to level and expand the playing field, balancing tradition with progress, actually calling out other members of the community including those in positions of power: instructors, games organizers, judges, stewards, etc., for bigoted jokes and comments, and actively listening to community members of colour so that we as a community become more inclusive and comfortable for all.”

“We could be doing more to recruit from areas that have more diversity and be more welcoming,” Owen Russell says. “Because you never know unless you try. What if there was an afternoon recital, and they saw people playing, and that sparked an interest. I mean, who wouldn’t be interested if someone like Reid Maxwell or Steven McWhirter just popped up and started playing – who wouldn’t be interested in something like that?”

Diversity across piping and drumming is not going to occur overnight, though. It will take time and proactive effort to welcome more into what appears to others as a closed shop.

Until female trailblazers like Gail Brown and Jennifer Hutcheon played their way into Scottish Grade 1 bands, and solo pipers like Patricia Innes (Henderson), Anne Sinclair (Johnston), Rona MacDonald (Lightfoot) and Anne Stewart (Spalding) persisted in breaking the gender barriers of the top competitions in the 1970s, women did not start to have a significant presence in our pastime.

And nearly 50 years later, women – who make up 51% of people on earth – still represent about a quarter of our hobby’s population.

But with enlightenment and the courage and the conviction to recognize and confront problems with solutions come change. Change tends to happen slowly in all walks of life, but in a piping and drumming world steeped in tradition and ethnic culture, the pace of change can be so slow that it is almost invisible.

Owen Russell sums it up. “Before you see a much more diverse range, it’s going to be awhile. But I hope I’m still playing when that happens.”

Our thanks again go to all who contributed to this piece, and to those who took the time to read it.

As always, we welcome your comments. We encourage you to post your thoughts through our own comments system, as they will stay with the story for good. Those posted to Facebook tend to be lost in the future.

Related

Is piping and drumming a welcome place for Black players? – Part 1

Is piping and drumming a welcome place for Black players? – Part 1

#MeToo: A collective call to members of our community

#MeToo: A collective call to members of our community

November 1, 2017

#MeToo

#MeToo

October 19, 2017

The status of females in piping and drumming in 2020

The status of females in piping and drumming in 2020

April 2, 2020

Enlightenment: Drummer Robbie Crow and piper Austin Diepenhorst on being visually impaired in a visual community

Enlightenment: Drummer Robbie Crow and piper Austin Diepenhorst on being visually impaired in a visual community

January 17, 2020

Great to see these pieces, I had wondered if we’d ever begin to think about these things–dealing with the consequences of BLM in academia has really turned the spotlight on privilege so it’s encouraging to see the debate open up in this forum. If you can’t recognise yourself in a community of practice, then it’s unlikely you’ll join, we need to be much more proactive in piping and drumming about diversity–not for ‘virtuousness-es’ sake–but because it will improve our music and our culture immeasurably.

Hi there, I tried to comment on the first part but was unable. Yes there is racism in the piping and drumming world. I experienced this and continued to experience it. Hopefully things will get better now that some of the privileged are “woke” to accepting that it exists.

Playing a musical instrument is a privilege and not a right. This privilege is for those who have money. If you want to include underprivileged individuals provisions need to be provided for them to have access to. Create programmes to help them get their feet wet do to speak. There are large school bands that provide access to musical instruments why not challenge these bands of Celtic affiliations to have a piping band. This in itself may generate more interest in piping and drumming. Why not try to present piping at a community level.

Try to make playing in the pipe and drums band a cool thing instead of it being only for the privileged.

Create charities in communities to offer tuition and take opportunities to profile your successes. This could and should make the piping community more more attractive to the underprivileged.