The Highland bagpipe in the COVID-19 era: what are the COVID-19 risks, and how can we reduce them?

By Ken Maclean

Editor’s note: To date, there have been no scientific studies specific to the Highland bagpipe and pipe bands and the potential spread of COVID-19. With pipe band practices and in-person competitions and performances shut down in most of the world, pipers and drummers are keen to know when it might be safe to get back at it. Some areas of the globe, like Western Australia, have enough confidence to resume in-person events. The RSPBA’s Chairman, John Hughes, recently asked bands to lobby their members of Scottish parliament to allow pipe bands to return to practice. Most of the piping and drumming world considered the move as irresponsible and even dangerous. Ken Maclean of Sydney, Australia, weighed in on a discussion with his research, including an alarming video of the aerosol effects from playing a practice chanter.

We contacted Ken Maclean to gauge his interest in expanding the discussion, and he has kindly provided a detailed three-part discussion of COVID-19 as it pertains to the playing of Highland pipes, the practice chanter, and piping and pipe band performance.

We stress that pipers and drummers should continue to take the utmost care in helping to mitigate the spread of COVID-19.

Part 1 of this series highlighted the traditional view of COVID-19 as being primarily a droplet and fomite (contact) spread disease. What is now understood is that exhaled particles that are smaller than the size of a visible dust particle (<100mm) can remain airborne for significant periods and are central to the spread of COVID-19 via aerosol transmission.

If aerosolized particles contain SARS-CoV2 virus, it is their small size that facilitates not only spread but the direct inhalation deep into the lung and lower airways. This facilitation effectively bypasses the first lines of “host defense”: the skin and critical parts of the immune system, notably the protective mucosal tissue barriers and lymph nodes within the upper airways (the mouth, nose, throat and larynx) that generally help to prevent or limit infection.

Aim

Throughout this series of articles, the intention is to try to draw together expertise, recognizing the need for a collaborative, funded approach for piping, schools, bands and the various peak bodies that incorporate lessons learned and expertise from recently published studies conducted in choral, woodwind, and brass musical ensembles. This expertise is not merely scientific – there is a role for those with artistic and communication skills to create graphics, TikToks, YouTube videos, and so forth, which simplify the messages, enhance their uptake and retention and promote sharing of ideas.

Part 2: Is the practice chanter the single most significant hazard?

Ask any pipe band drummer, and they will tell you that sitting next to or opposite a piper during chanter and drum pad band practice holds little allure. The “flick” of the chanter in bygone days let everyone know that the practice chanter was a “wet” instrument. The “spray” evident on their drum pad attested to the visible ‘ballistic’ dispersal of droplets – sometimes palpably so for those sitting too close. For the piper’s themselves, there is a frequent need to wipe down their hands after handling the chanter during practice, or as any piper tutor might observe, watching young learners use their jumper or jeans to clean their hands, face, chanter and chanter reed.

This article focuses exclusively on the practice chanter. There are several reasons for this:

- The practice chanter is an everyday part of pipe practice and pipe bands.

- It is the entry point for all piping tuition.

- Its relevance to young people, school and juvenile bands equates to the need for clearly defined standards of governance in 2020.

- There are data and guidelines available on analogous systems, e.g., clarinet, flute, saxophone, etc. (Credit to Dr. Shelly Miller Environmental Engineering Professor CU and the NFHS team.)

Further information

Performing Arts Aerosol Study and video

- Chanter practice almost exclusively occurs indoors.

- Concepts of the built environment, ventilation, practice room sizes, etc. are relevant.

- It is a more straightforward system to model than the Highland bagpipe.

- It offers the opportunity for a staged return to piping, teaching and pipe bands.

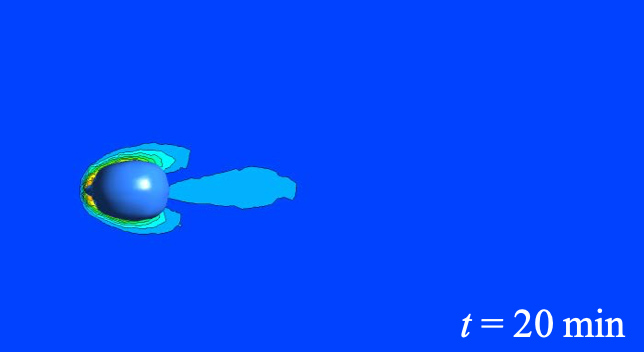

In considering the practice chanter, the balance of risk is probably to a greater extent weighted towards droplets and fomites as compared with aerosols that predominate with the Highland bagpipe. While aerosol production via the practice chanter is demonstrable (see video), an important question often asked is the relative risk. This is to say how much more hazardous are aerosols emitted via the instrument versus those with everyday activities such as normal respiration, talking, speaking loudly, light activity, and voice projection, e.g., singing or shouting.

Positively, many measures can be easily applied to the practice chanter to promote cleanliness, hygiene and effective decontamination/disinfection. Many of these build on the knowledge that has become commonplace over the last six months. What needs to be better understood is how they might alter the “microbiome” – the sum total of viruses, bacteria, fungi and moulds – that might usually be present in an individual’s practice chanter. By extension, can we define if the practice chanter and chanter practice pose an acceptable or unacceptable hazard for the spread of COVID-19 amongst attendees? The article quoted in the previous review showed how simply maintaining the cleanliness of a cane reed reduced the microbial flora by many orders of magnitude for a saxophonist.

Can we effectively mitigate these risks?

Before detailing the specific risks of the standard practice chanter, it is essential to consider a broader perspective and, in particular, strategies that have been adopted and endorsed already by pipers and pipe bands in response to the pandemic.

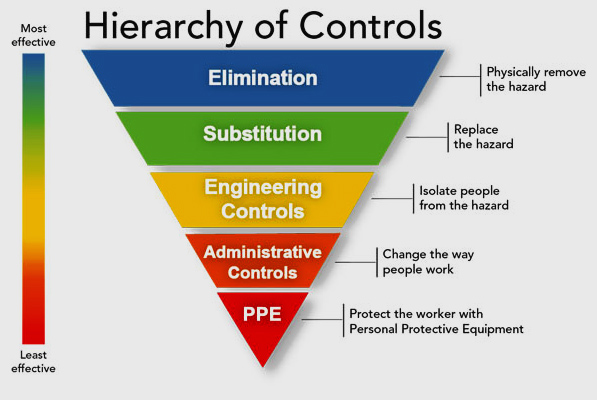

Engineering models termed prevention through design, utilize a hierarchy of controls to implement feasible and effective disease control solutions to prevent infection. There are a surprising number of well-designed engineering controls that remove the hazard at the source that can be easily implemented and are useful in decreasing the risks to pipers and ensembles. A key concept is applying the precautionary principle as compared to an abundance of caution.

Engineering controls

Elimination: This requires the piper to stop practicing. Not practicing, as pipers, spouses, partners, children, pets, neighbours, and indeed anyone near a piping household will attest to, is not possible.

It is essential to know how many pipers and drummers might have stopped playing, practicing or learning and, if so, how these individuals view re-joining band practices when safe to do so.

It is especially critical to know how the pandemic is affecting our younger pipers, from novices through to elite juvenile pipers and bands. This knowledge requires data and feedback via school, youth and teaching institutions as well as online and social media monitoring and feedback.

Are established pipers and drummers turning to their chanters and pads more during the pandemic? If so, what is their motivation? Is it a habit, an earnest desire to practice, or a result of the ever-present anxiety that is affecting so many in 2020?

Substitution: Replacing the hazard

There are two fundamental approaches in this regard for the practice chanter.

- Online practices that altogether remove the face-to-face component.

- Electronic practice chanters that eliminate many of the hazards of face-to-face chanter practice and teaching.

These approaches are:

- Group/ensemble practices.

- Individual (1:1) practice/tuition sessions.

Online chanter practice sessions in preference to face-to-face practices

- This will continue to be important as the pandemic continues.

- It entirely nullifies the risk of COVID-19 b/w teacher and student/ensemble players.

- It avoids the complacency in COVID-19 precautions that occurs in face-to-face teaching.

- It is convenient for all parties.

- It requires minimal set-up.

- Individual platforms have their pros and cons, e.g., Zoom, Microsoft teams for ensembles, Facetime/video sharing apps for individuals.

- It requires familiarity with the individual platform (and punctuality).

- A significant problem is an acoustic delay that limits its utility with ensemble practices and in seeking to play along with a teacher or student.

- Typically the delay equates to ~20msec latency. While there are approaches that may help to reduce the delay, none will completely solve this problem.

- We should expect this to be a permanent fixture in practice chanter and band tuition.

- It cannot replace face-to-face teaching and face-to-face ensemble practice when this is permissible.

There is a unique opportunity for pipers of all levels to access lessons from experienced tutors and accomplished younger pipers. This accessibility can yield great dividends for piping and collegiality. It is a way to help out those whose livelihoods are impacted, be it professional tutors or younger members of the piping community. They may not be able to access part-time or casual work. Speaking from recent experience, there is nothing better than learning from a new tutor to help your piping, increase your repertoire and, overall, to boost your enjoyment of playing.

Electronic chanters as a face-to-face practice tool

Most owners of electronic chanters are likely experienced pipers. Examples are the Blair Digital Chanter, the Deger chanter, and so forth. These are of use for face-to-face and online practice sessions. The recent work of several bands, including the Grade 1 St. Laurence O’Toole, has showcased how well they mesh with the traditional practice chanter in an online performance that utilizes post-production editing.

There is a case for the purchase of electronic chanters for school and youth ensembles – assuming that organizations and parents can fund the investments. The purchase of additional devices by schools, music teachers or pipe bands could facilitate safe face-to-face practice sessions for young players.

It is outside of my expertise to know how the technical aspects of these devices – the optical-based recognition of fingering and execution – affects the sensitivity for note-errors and basic fingering technique as compared to the standard practice chanter. The question relates to its utility for face-to-face teaching sessions for learners and novice pipers in achieving an adequate sound (versus virtually no change in sound if the note error is large).

That they work with headphones makes them a valuable asset for solo practice, be it in the home or a shared community environment. It is particularly relevant given that many people are working from home, children may be doing distance-learning, and in general, the intolerance towards other’s musical practice may increase by virtue of the occupational and mental health stresses of COVID-19 lockdown. This intolerance is amplified with those living in units and apartments.

The cost and, to a lesser extent, availability and supply of electronic chanters are barriers to their widespread adoption. Until they reach a price to a level nearing that of standard practice chanters, it isn’t easy to perceive their general use. They are easily cleaned and, by removing the mouthpiece on the Blair Chanter, the potential for fomite spread of COVID-19 assuming simple hand hygiene and surface disinfectant is low.

Electronic chanters are an ideal substitute for ensemble practice and 1:1 tuition with the following provisos:

- Separate instruments for teacher and student.

- Appropriate instrument (surface) disinfection precautions – pre- and post-practice.

- Hand hygiene precautions.

- Physical distancing.

- Masks – throughout.

- Adequate room ventilation.

- Remove the mouthpiece from a student’s instrument.

There is the potential, depending on the set-up, for real-time recording, e.g., via laptop, GarageBand, etc., for the student or teacher to edit and listen back to at the time or later.

An emerging question is how to use technology to facilitate real-time ensemble practices via online sessions using electronic instruments. This question is part of a broader dilemma for both analogue and digital instruments in the era of online musical ensembles.

Isolating people from the hazard

It is important to reiterate that anyone who is sick, awaiting a COVID-19 test result, in contact with a positive case or, indeed, a person who has recently tested positive, should not attend a practice or be in face-to-face contact with band members who do not share a household.

It does raise the question of how to deep-clean the practice chanter of an individual who has tested positive. This deep-cleaning is critical and is reasonably straightforward using simple detergents with vigorous brushing of internal and external surfaces, plastic reeds (if not disposal/renewal), and sun-drying with ultraviolet light exposure. Only use products that are known to be safe for the instrument and the piper’s health. Fifth-generation silane quats – available as commercial cleaning sprays – provide a useful adjunct to maximize microbial, cellular and viral disinfection. Take care to allow any cleaning product to dissipate fully before blowing, to minimize the risk of accidental inhalation that could trigger asthma-like symptoms in susceptible individuals, and always read the pre-delivery inspection instructions.

Administrative controls can include reducing the number of attendees per session, avoiding unnecessary attendees, splitting a pipe corps and not having both pipers and drummers at individual sessions.

We can reasonably anticipate that the guidelines based on physical distancing, e.g., 1.5-2 metres social distance, one person per four square metres, may change based on updated advice on aerosolization and risks as they relate to the built environment.

Changing the practice environment to outdoor practice venues, conditions permitting, is an ideal option for those bands fortunate enough to be in warmer climates. This change is encouraged, since outdoors – particularly in the presence of a breeze (>4km/hr) is sufficient to disperse aerosols rapidly. There are data on aerosol dispersal in tents, which may be relevant to those using a marquee.

Indoor environments should be well ventilated or air-conditioned with appropriate air filtration systems (HEPA, MERV13+) that remove small particles. Practice rooms at schools are often small, e.g., 2.5 x 2 x 3 metres with a small volume (about 15 square metres).

Ideally, a room should have approximately one air exchange per 10 minutes – a level at which the build-up of aerosols is not anticipated.

CO2 monitors can provide a proxy or marker of air exchange (normal 500-600 parts per million). These are advocated for schools and commercial music premises (cost ~$200).

Mouth-blown practice chanter, face-to-face practice – 1:1 and ensemble practices

While not seeking to promote an individual manufacturer, Twist-Trap pipes are a noteworthy recent innovation that provides an excellent intermediate instrument that can be adapted for ensemble chanter practice for bands.

They are essentially a “low residue” device as compared to the Highland bagpipe. Simply stoppering the two drones (or, potentially, from the manufacturing side, creating a stopper to take the place of the drones) abolishes aerosolization from the drones. The instrument is easy to blow (and to overblow!), and with the twist-trap device and the relatively large-volume bag reservoir, it is not unreasonable to presume that the risk of aerosolization of live virus from the chanter is low, potentially comparable to speaking. Given the ease of the instrument, the likelihood of spray from the mouthpiece for an experienced piper will be far less than for the practice chanter or Highland bagpipe (see below re masking while playing). The price of Twist-Trap pipes is less than an electronic chanter. They offer an opportunity for bands to play together with relative safety on pads and chanters, assuming appropriate environmental conditions.

Traditional practice chanter (see video)

- Hazards: direct and indirect contamination from oral secretions via the chanter.

- Inherently moist environment.

- Condensation within the instrument at the finger pads.

- Aerosol spread from the mouthpiece, bell and key-holes.

- Dispersal – multidirectional, including upwards.

- “All of us having a personal cloud” located around and predominantly just behind your head.

- It extends only about 1-2 feet behind.

Fomite transmission onto hands, furniture, music books, surfaces, etc. (fomites) with oral secretions likely, given the volume of saliva produced and the ease of spread of secretions.

- Mouth-blown.

- Typically becomes wet after a few minutes.

- Likely production of many millilitres of saliva in any practice session.

- A source of dispersal of droplets and aerosols via blowing, including overblowing and long “gulping” breaths with forced exhalations, often at the end of a part.

- Circular breathing does not remove the hazard.

- Need to disassemble standard practice chanters, upended – not “flicked” – to remove the collected saliva from around the reed.

- Use the bathroom sink or an outside tap instead.

- Emptying secretions only onto absorbent surfaces only, e.g., “puppy pads” or absorbent “bluey” pads, one for each player, away from others if needing to be done in the practice room.

- Wash hands and wipe down the instrument before returning to the practice room.

- Wrap the chanter in a towel and clean the instrument at home.

- Use a fresh towel for each practice.

- Engineering approaches can reduce the amount of saliva coming in contact with the reed, reduce the need to open the device and to handle the reed, e.g., Twist-Trap chanters.

- This is akin to the handling of secretions with a saxophone or trumpet with spit traps, and potentially such designs could be further enhanced.

- Encouraged for new learners purchasing their first chanter.

- Hand-wash/sanitizers/sinks/soap should be available for each piper and used frequently.

Personal protective equipment

Personal protective equipment is the last line of defense.

- In preference to face shields for pipers – to stop the spray emanating from the mouthpiece becoming disseminated – standard surgical masks with a hole in them have been trialed by woodwind and brass players. These are highly effective, but adaptation takes time.

- Masks use for attendees not playing is critical.

- Band tuners and pipe-majors should give extra consideration to their hazards and personal protective equipment, e.g., masks, face shields.

- Standing behind a person playing with or without a mask is to enter their “personal cloud.”

- Hand-wash/sanitizers/sinks/soap are essential and need to readily available.

Part 3 of this series will focus on the Highland bagpipe, simple strategies to maintain instrument hygiene, and the far more challenging topic of defining the extent of aerosol generation. Aerosols generated from the Highland bagpipe might likely contain live SARS-CoV2/COVID-19 virus. It is possible to mitigate against the hazards effectively. It is increasingly apparent that developing effective responses to aerosol spread poses the most significant hurdle for the return for pipers, tutors and pipe bands.

The author would like to acknowledge Bradley Parker for his help with this series.

Stay tuned to pipes|drums for the third and final part “The Highland bagpipe in the COVID-19 era” when Ken Maclean tackles problems that playing the Highland pipes in the presence of others present.

Ken Maclean is a medical specialist in genetics and pediatric medicine based in New South Wales, Australia. His clinical experience means that he has seen firsthand the devastating effects of viral illness in children and families. He is a piper happily enjoying staying safe and improving his piping during the pandemic. Ken has been closely following the literature and community advice on COVID-19 and, in particular, the subject of aerosol science as it pertains to woodwind musicians and ensembles. His goal in giving to back to the piping community in the form of up-to-date evidence and science-based advice. He is active on twitter (@kenpcg) and regularly contributes to online discussions of piping safety in the COVID-19 era.

Related

The Highland bagpipe in the COVID-19 era: what do we need to learn?

The Highland bagpipe in the COVID-19 era: what do we need to learn?

August 31, 2020

RSPBA advocates for pipe band exception to COVID-19 restrictions

RSPBA advocates for pipe band exception to COVID-19 restrictions

August 16, 2020

NO COMMENTS YET