The Drum Corps Conundrum: Four drumming greats discuss the ongoing battle to recruit snare drummers and L-Ds – Part 1

For as long as pipe bands have existed, one problem has refused to go away: the struggle to find enough snare drummers and leading-drummers to keep bands thriving.

All over the world, bands that were once strong and competitive are now stepping back from the field – or disappearing entirely – simply because they can’t fill their drum corps. And yet, in a world rich with percussionists of all kinds, how can this be?

We wanted to explore that question honestly. Not with a survey, not with an editorial, but with a conversation, open, unfiltered, and led by people who understand the issue firsthand.

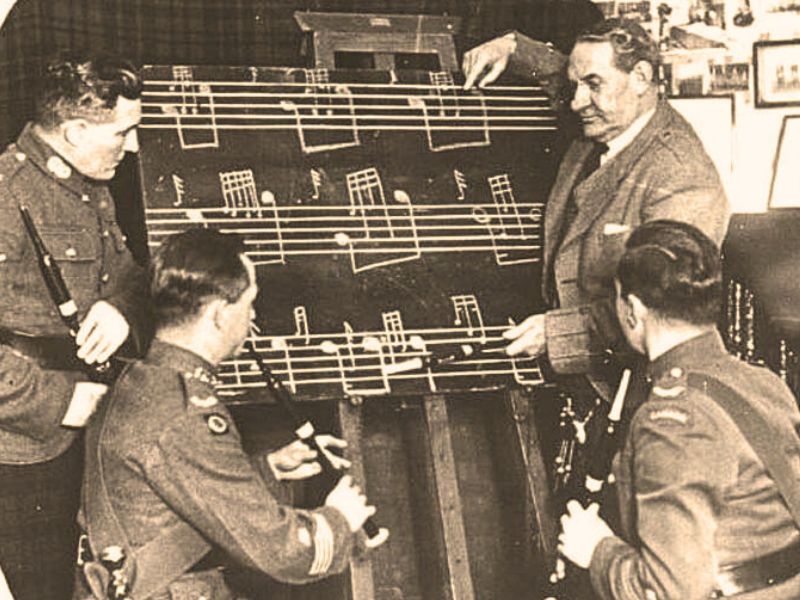

We brought together four of the most accomplished pipe band drummers of the last several decades, representing different countries, experiences, and eras of the art.

From Boston, Scott Armit brings years of leadership and judging experience, having headed the Grade 1 Stuart Highlanders and Manchester Pipe Band corps, and is currently the leading-drummer of the Commonwealth Pipe & Drums of Massachusetts. His father, Davey Armit, was one of the United States’ greatest pipe band drummers, and Scott is a judge with the Eastern United States Pipe Band Association.

From Ottawa, Kahlil Cappuccino adds the perspective of a celebrated bass drummer whose own Grade 1 band, the 78th Highlanders of Halifax, has been forced to take another year away from competition because it couldn’t recruit a suitable leading-drummer. He has won numerous North American Bass Section Championships and is in high demand as an instructor and judge.

From Blairgowrie, Scotland, Paul Turner offers a global view shaped by leading four Grade 1 corps: Royal Ulster Constabulary, Victoria Police, Dysart & Dundonald, Grampian Police, and Vale of Atholl. He won the World Solo Drumming Championship in 1989, and He now serves as one of the world’s most respected judges and in-demand instructors.

And from Troon, Scotland, Barry Wilson contributes his insight as one of the greatest snare drummers in history: a four-time World Solo Drumming Champion, a 15-year member of Shotts & Dykehead Caledonia, the leading-drummer of ScottishPower for 12 years, and a member of the 2016 edition of the Grade 1 Spirit of Scotland band of all-star players.

For this discussion, we stepped back entirely. No interviewer. Just four pipe band drumming experts, guided by Kahlil Cappuccino, talking candidly about why snare drummers can be scarce, why leading-drummers are so hard to recruit, what challenges today’s bands face, and what meaningful steps might reverse the trend.

What emerged was too valuable to pack into one episode, so we’re presenting their conversation in four parts, each with lessons that leaders, judges, teachers, pipers, and drummers at every level can learn from.

This is the beginning of that discussion: a clear-eyed look at the shortage of snare drummers and leading-drummers, and the ideas that just might help shape a stronger future for pipe band drumming.

For those who also enjoy reading, here’s the transcript of the discussion:

Part 1

Kahlil Cappuccino: Alright, so we’re trying to unpack this whole conundrum around the seeming lack of leading-drummers and drummers who are prepared to step up and take on the reins of corps. It seems to be a problem that’s been around since, well, since I’ve been playing in pipe bands, which is almost 40 years now. What might the problem be? Is it a problem? And why is it? And do you agree that’s a problem? Paul, let’s start with you.

Paul Turner: Over the years, the requirements haven’t changed, but people’s work life, family life and band life balance because the band life is the fun part. That has changed quite a bit, making it more comfortable for drummers.

It’s so difficult, at any level, if they’re comfortable playing under a leading-drummer in a band that they’re enjoying the music, when they look at what would be required and the commitment would be required, people balk at it slightly.

Kahlil Cappuccino: Regardless of the music genre, you suddenly become the jack of all trades. You need to be able to be the tour manager and the production manager and the person who holds somebody’s hand when they’re having a problem, and to field all the issues that come at you and the reasons or the excuses for not being able to make it out and keeping a corps together.

And then just add that I would say, you know, I’ve been playing in the Halifax band for almost 20 years, and as you know, we’re on a bit of a hiatus, and I quite enjoyed last summer. You know, I got to go and go to music festivals that I haven’t been able to go to in 20 years. So there’s things that make for more compelling argument to not be part or not lead. And I’m wondering, Scotty, maybe you want to just sort of expand on that and what your thoughts are.

“It’s a ton of work being a leading-drummer. It feels almost like a second job sometimes. It’s in my brain as much as my job and my family are.” – Scott Armit

Scott Armit: Yeah, I agree with both of you. And, you know, for me, having kids really changed that quite a bit. I had a big push in my younger years, and then the kids showed up, and being a leading-drummer feels like a second job. Then you’re in the heart of your career, maybe. And then you add kids to that. I didn’t quit, but I took a little break from pushing at the higher levels, trying to get to Grade 1 or even Grade 2, and playing with lower-grade bands was easier. Now my kids are grown, I’m going back, and I’m remembering just how much work it is. I’m trying to make another push into Grade 2 at least, and it’s a ton of work being a leading-drummer. It feels almost like a second job sometimes. It’s in my brain as much as my job and my family are.

Kahlil Cappuccino: And Barry, when we were kind of chatting before, you were talking about golf and how you like hit the links. And when you compare that to your days of leading the Power. Or your 11-plus championships with Shotts as a corps drummer, and as a leading-drummer, what are you seeing? How are you feeling about all this?

Barry Wilson: It’s not something new, that’s for sure, but it’s got worse. I don’t think it was as bad as it was, maybe 20 to 30 years ago. But certainly, it’s manifested more now due to the size of corps. As we’ve all spoken about, family commitments. That’s one of the reasons I left was to start my own business and have a young family.

To be honest, the drive wasn’t there, and it’s not fair. If the leading-drummer doesn’t have the drive, you’re letting everybody down in that band, so there’s no point in being there. So yeah, there’s a whole combination of factors that you have touched on there. Certainly, I’ve noticed since coming away, I don’t think I could go back to it because of the time commitment. And it’s not until you step away that you realize just how much it consumes your life.

Kahlil Cappuccino: It’s interesting. Does the paradigm need to shift from almost that full-time drive for excellence to something else, to is it just good enough? You picked up the sticks for Spirit of Scotland for a season, and I would presume that that might have been a nice sort of way to keep your hands going, but you didn’t have to do all that is suggested of a lead-tip.

“It’s easy being a soldier; it’s hard being the general.” – Barry Wilson

Barry Wilson: No. I got a load of messages at the time. Guys I’m friendly with – a bit of banter and a bit of a needle-poke, you know, “I thought you were retired and now you’re back playing!” There was a bit of joviality about it. As I said to them all, it’s easy being a soldier; it’s hard being the general. And that’s how I felt. Give me the music, I’ll learn it, I’ll show up to a practice, I’ll play.

I loved that. I hadn’t done that for 12, 13 years. So, going back to do that was a breath of fresh air. I don’t want to do it for any length of time. It was all right for a year. But it’s a massive undertaking being a leading-drummer and a pipe-major. For the things that you’ve alluded to, you need to be a mother, a father, an HR consultant, a counsellor. You need to be everything to these people.

Kahlil Cappuccino: It’s interesting, in my experience, in some ways, I was in a really good place. There’s only one bass drummer. You’re like a goalkeeper in football or hockey. I moved from going to, say, two to three weekly practices to one weekend a month, and an hour-and-a-half plane ride. It was ideal because it left me time to help raise my kids. I could take my son to hockey, I could take my daughter to dance, and it was there.

And now that Halifax is on the bit of a pause, I’ve been approached in other instances to come shore up a place. But it’s not as compelling for me. My wife and I were talking about it. I said, “Do you realize that if I do this, I’m going to be out two to three days a week for rehearsals and stuff?” And I’m not sure I have the drive to do that anymore, at any rate.

Paul, the Vale, Victoria Police, how did you manage that? When you look at who you had in your corps, did you have any thoughts about succession planning or building the resilience of the players who were there to become the next generation of leading-tips?

Paul Turner: I’ve been lucky in any of the corps that I’ve been lucky enough to lead; there’s been a very good talent pool, and there’s always been one or two who stood out as prospective leaders, both from their playing capabilities and their general personality and their own personal drive.

When I stepped away from the Victoria Police, the natural successor was Harold Gillespie. He had been my right-hand man for four or five years. And before that, he had been the right-hand man for Andrew Scullion, my predecessor. So that was a natural progression.

Prior to that, Andy succeeded me in the RUC days and in the old black-and-white days in the ’80s. There’s always been somebody there. I’ve been lucky. When I was at Dysart, I had Gordon Lee, who was an up-and-coming superstar, and he subsequently went to play for Reid [Maxwell] at SFU.

And after my second time at the Vale, Crawford Allen helped me through a lot of tough times because it was full-on for six years. Crawford was a natural fit, and it was seamless. It was spotting talent, spotting somebody with a drive and giving them more responsibility on a practice, on a weekly basis, on a monthly basis that helped spread the leading-drummer’s load that I had. But it was letting people see that, if you go down this route, you’re not going into it blindly. Here’s a taste of what you’re going to see.

“Anybody who doesn’t pre-plan is risking the band.” – Paul Turner

And if you look at the most recent changes within drum corps and pipe-majors in the top bands, there’s been quite a substantial change in the last four or five years. Every one of them has had somebody waiting and ready to take up the reins, whether it is pipe-major or leading-drummer

Anybody who doesn’t pre-plan is risking the band.

Scott Armit: I’ve tried it three times with varying success. When the Stuart Highlanders were upgraded to Grade 1, it was terrible timing. It was a dream to get upgraded to Grade 1 for me, so I helped build the band up to do that. And then when we got it, like we mentioned earlier, was right when I had twin daughters turning about three years old and my career taking off.

I handed it over and that worked out for a little while. But Paul’s exactly right. To be able to do it is difficult. When I’ve tried it in the past, there are great drummers who don’t want to be or aren’t good at the other parts of being a lead. You try to identify them in your corps, but I’ve had guys playing with me for 25, 30 years now and I’ve said to some of them, Hey, I need a break. Why don’t you do it? And they say, No way! So, there is that, too. It sounds like Paul’s been lucky with it, but I wasn’t so lucky. I was lucky to have great drummers and continue to have great drummers, but most of them do not want to lead.

Kahlil Cappuccino: Scott, I remember your Manchester corps in the 1990s. We’re aging ourselves there, but you would put out powerhouses. I noticed you had the same corps of people with you. And I saw that with the Stuart Highlanders and Commonwealth. Why do so many drummers move in packs? Does it have to do with comfort and maybe confidence in the leader?

Scott Armit: A big part of it is the style. I’m not knocking pipers here, even though, as drummers, we love to do that, but we’ve all seen that pipers are a little more plug-and-play. They open the Scots Guards Collection, find a tune, send it out by email, and say, “See you in June.” I know it’s not that simple, but it’s easier for them to show up, where most of us leading-drummers develop a style, and we have a technique. I’m all about movement and technique.

I’ve brainwashed some of these guys – I don’t think they’ll mind me saying that – over the years. Like, No, please, Swiss ruffs this way. Play this way every time. Play it this way. And then if they branch out or even look at another corps, they say, I’ve learned to play it this way. I don’t like the way that other corps plays it. That’s part of it.

The other part is that we’ve worked so hard together and become really good friends. So, you tend to stick together. Those are the two biggest things: style and working so hard together over so many years, you just stick together.

Kahlil Cappuccino: Barry, how did you find it without your really good corps?

Barry Wilson: I can quote from my long past history when I was approached to take over ScottishPower. I had been in Shotts for 15 years up to that point. A bit of panic set in because it was like, I don’t have a drum corps! I don’t think any of the existing guys are going to hang about for this young whippersnapper to come in and do stuff. I didn’t necessarily have a drum corps to inherit and, at that time, I actually approached a few of my closest pals in the Shotts and said, “Listen, would you?” And two or three of them decided they wanted to try something new and come support me.

“But they do tend to hunt in packs, drummers. And being loyal is probably the biggest thing.” – Barry Wilson

And as Scott alluded to there, it’s about the friendship thing. There’s a big bond you build up with these guys over the years. These guys who came with me, I’m still friends with them to this day, and we still keep in touch even though I’ve not been playing and they haven’t been playing for a while. So, there is camaraderie amongst us. I’m not saying there’s not a camaraderie amongst pipers, but it’s maybe more so amongst the drummers for the reasons that we’ve spoken about.

The guys tend to stick together. They like the way you do things. You enjoy each other as people, which is half the battle. If you’ve got a guy you just can’t stand, there’s no point in being there. So, there’s a whole host of factors.

But they do tend to hunt in packs, drummers. And being loyal is probably the biggest thing.

“It’s much easier as a bass drummer, but it would take me a few months to understand the preferred phrasing and expression that a certain lead-tip would like. – Kahlil Cappuccino

Kahlil Cappuccino: From a bass drummer’s perspective, I’ve been through a number of leading-tips in various bands. Some have departed in the middle of the season; some have departed right at the cusp of a new season. But I always found that, even as a bass drummer, I had to relearn the stylistic preferences of each leading tip. I found it would take me – and it’s much easier as a bass drummer, but it would take me a few months to understand the preferred phrasing and expression that a certain lead-tip would like.

I guess that speaks to it as a snare drummer, which I did do for a while. I understand that comfort-level going forward.

Stay tuned for Part 2 of “Getting to the core,” our panel discussion with four of the world’s greatest pipe band drummers, coming soon.

What are your thoughts? Please use our Comments feature to provide your observations and opinions!

Excellent, real-world stuff there.

Great topic and panel! Looking forward to Part 2.

One aspect of competition that has not yet been touched on is the lack of any restriction on the maximum size of drum corps in competition pipe bands.

Impressive as the large numbers can be, we can’t ignore that with so many great players being drawn into the current mega-corps in Grade 1, or even Grade 2, the lower grade bands, and ones that may well have bright futures on the competition field, simply can’t find leadership, field a band, or expect to place if they do so with their smaller numbers.

Numbers don’t mean excellence, but related to our discussion, I believe that numbers can have an overall influence detrimental to smaller corps.

Musically, is it more difficult to try to blend, say, 9 sides over 5? Sure. It requires talent and practice. And, it can be awesome to hear!

But, with pipe band competition, in terms of creating level playing fields the establishment of minimum numbers without also imposing maximum limits just doesn’t make sense.

And, related to the discussion, I believe that this lack of parity is a contributing factor in recruiting, and keeping, enough drummers for the smaller bands to be able to compete.

IMHO!