Guest opinion: Strength at the top, strain below – regulate max numbers before it’s too late

For more than 20 years, pipes|drums has discussed the potential problems posed by unregulated numbers of players within pipe bands. We were pleased to receive this thoughtful opinion piece from one of the world’s best pipe band drummers. The opinions expressed are not those of pipes|drums. They are presented here to create constructive dialogue and, if it makes sense for the piping and drumming community at large, positive change.

By Scott Armit

The Growing Divide

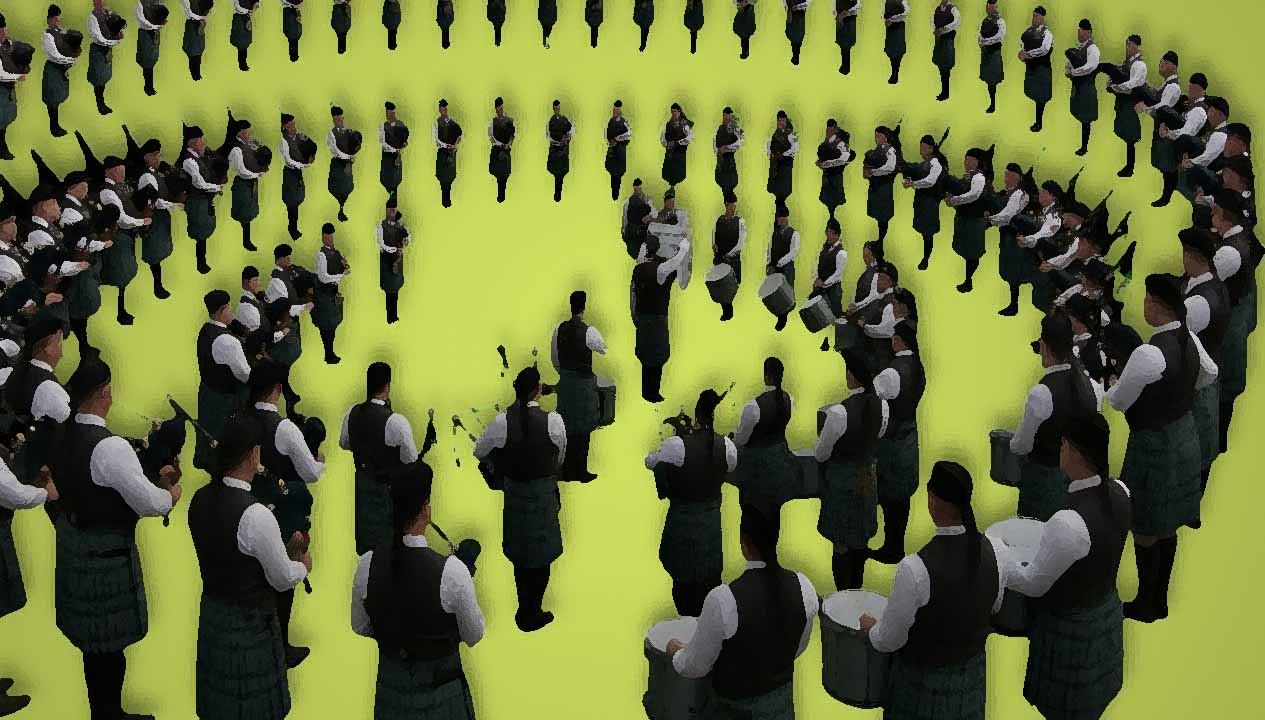

At this year’s World Championships, the Grade 1 bands that finished in the top half averaged 11 snare drummers, while the lower half averaged eight. Two of those lower-placed bands have since declared themselves disbanded, and earlier in the year, another in the top flight took the season off, citing difficulty in finding a leading-drummer.

The contrast is striking. The top drum corps field more players than ever, while capable bands below them struggle to find leadership and fill their lines to match those at the top. Many of those larger corps include players who could lead elsewhere but face a choice: join a powerhouse with a real shot at victory, or pour time and energy into a project that, against such size, is almost certainly doomed to fall short.

Seeing this as bad luck or leadership turnover is tempting, but the deeper issue is structural. With no maximum numbers in competition rules, the biggest bands can keep growing while others can’t keep up.

“Back in my day . . . “

At the risk of sounding nostalgic, back in 1995, my corps won the Grade 2 World Championship drumming prize with only four snare drummers. Even then, that was considered a small line, but our result proved that it was possible. We knew we could match larger corps, as their size wasn’t intimidating enough to keep us from competing. Many of the great drum corps of the recent past won the World Championships Grade 1 prize with six or seven snares, and it’s fair to say that some of them were just as good, or even better, than today’s larger lines.

Today, I wouldn’t even consider taking a Grade 3 band, let alone a Grade 2, to the World Championships with only four snares. In 2011, when I led a Grade 2 corps back to the World’s, we had nine sides. The trend towards larger corps was already well underway. However, we couldn’t sustain this in the long run, and ultimately, like others today, we fell by the wayside as numbers dwindled and the talent pool in our region of the U.S. proved too small.

We’ve all witnessed the consequences for Grade 1 bands that attempt to compete with six or seven sides. What can an adjudicator really do when comparing seven against 13? The landscape has changed so drastically that a line of that size is already at a disadvantage before even playing a single note.

Gravity

Playing at the highest level demands relentless work, individually and as a corps. For players who have put in the effort but find themselves in a band that lacks the numbers to compete with the top tier, the pull of the bigger bands is strong. When a respected leading-drummer says, “Maybe come play with us next year,” it’s hard for any ambitious player to resist the chance at a World Championship prize.

In the United States, this challenge is familiar. Building a solid Grade 2 band is difficult, and sustaining a Grade 1 band is even harder. Many of the best U.S. players have joined top-tier bands overseas for a shot at winning a big contest, while others have stayed home to build something local. Some have succeeded locally, but maintaining momentum is hard. The season can collapse when a corps loses one or two players, or when a few can’t make the big trips. Suddenly, everyone looks around and says, “Let’s skip it this year. We don’t stand a chance against 13.”

“The temptation to step back, join someone else’s big line, and share in their success is real. After years of building local corps at different levels, it’s hard to deny the pull of the top flight.”

Leading a corps takes real dedication. It often feels like a second job in the upper grades, with hours spent writing scores, running rehearsals, communicating, and maintaining high standards. When a prize seems out of reach, it’s easy to question whether the effort is worth it.

The temptation to step back, join someone else’s big line, and share in their success is real. After years of building local corps at different levels, it’s hard to deny the pull of the top flight.

The imbalance isn’t just about effort or geography; it’s built into the rules themselves, where a chance at success often depends on how many players you can put on the line.

Minimum without maximum?

A primary reason we’re seeing strong Grade 1 bands fold is the absence of maximum-size limits. This isn’t a new idea, but it deserves serious consideration given the shortage of leading drummers and drummers in general. Setting clear maximums for each section would help restore balance. Is there another competitive endeavour that doesn’t set limits on participants? Eleven v. seventeen soccer, anyone? Setting limits is the essence of fairness: your best nine against our best nine. It would force difficult choices within bands, but it might also motivate players to strengthen programs closer to home.

“Setting limits is the essence of fairness: your best nine against our best nine. It would force difficult choices within bands, but it might also motivate players to strengthen programs closer to home.”

Outside the heart of the pipe band world, in the United States, Canada, New Zealand, Australia, and beyond, assembling and sustaining a snare line big enough to match the top bands is an even bigger challenge. The local talent pool and sheer geography make it difficult to support large corps year after year. Reasonable caps would bring stability. Bands could focus on the quality within their lines instead of chasing numbers just to stay competitive. Many already have the skill; they’re missing only the headcount. If the largest line you might face were nine sides, maintaining, say, seven sides would feel achievable rather than discouraging.

Sustainability over spectacle

We’ll keep losing bands unless associations set upper limits that restore competitive balance. Competitive pipe bands have always thrived on excellence, not excess, but if the structure continues to allow unlimited size, more bands will vanish before the music even starts. The recent Grade 1 dissolutions aren’t anomalies; they’re warnings.

“The recent Grade 1 dissolutions aren’t anomalies; they’re warnings.”

This isn’t an indictment of the top bands. They are undoubtedly exceptional, but the current conditions make it nearly impossible for others to compete on equal terms. The result is a top-heavy system where a few bands can fill every spot twice over, while others wonder whether it’s even worth trying.

There will always be disagreement on this issue, and it’s not a new debate. Still, with Grade 1 bands disappearing, why not give it a try? Setting reasonable maximums won’t instantly make every drum corps and pipe band a World Champion contender, but it would at least give them a fair chance to compete on level terms.

Scott Armit is the lead-drummer of the Commonwealth Pipes & Drums of Boston, and was previously the lead-drummer of the Stuart Highlanders, taking his drum section to winning the Grade 2 qualifier at the 2011 World Championships, and helping the band to a fifth place overall in the final. He won multiple North American Professional Solo Drumming Championships in the 1990s and 2000s, and took the Manchester Pipe Band drum corps to a win in Grade 2 at the 1995 World’s. He’s a former Eastern United States Pipe Band Association panel judge. He lives in Boston.

Further information

Opinion: If there were ever a time to cap numbers, it’s now

Is the World’s killing the pipe band world? Part 1

Is the World’s killing the pipe band world? Part 2

The Matter of Band Size: Alex Gandy & David Wilton – Part 1

The Matter of Band Size: Alex Gandy & David Wilton – Part 2

Pipe Band Size Matters Debate: Armstrong and Livingstone take sides

Size Matters: Armstrong and Livingstone to square off in great debate

What do you think? We always welcome your fair opinions, so please feel free to use our Comments tool below, which is available to all registered readers and subscribers.

Yes. Yes. And, yes.

And the sooner the better.

I used to be of the opinion that size limits unfairly penalize organizations for simply developing a strong program that attracts players, but I do believe that more bands is better than bigger bands. I don’t think in the US we will see another G1 or G2 band just because of some 9 snare maximum, but in Scotland maybe that’s more possible…I don’t necessarily care about creating greater parity by handicapping the best programs, but if reasonable number limits convince more bands to show up, I’m for it.

As a comparable example, DCI (Drum Corps International) has a maximum number set for its participating Corps. Though they do not specify a maximum number for each unit within the Corps. So this may at least be a first step.

Since the current minimum for Grades 1 through 3B is is stated by RSPBA rules as “8 Pipers, 3 Snare Drummers, 1 Bass Drummer,” why not try changing the rule to state:

5. Number of Performers

The number of performers that can be in a Pipe Band is defined for Major Championships and Minor Competitions:

• Grade 1 – 3B: minimum 12, maximum 36

• Grade Juvenile – 4B: minimum 9, maximum 28

Not specifying the size of pipe and drum sections.

An excellent article.

If there’s one thing I’ve learned over the years, it’s this: pipe bands don’t owe us—but we all owe something to the health of the community.

Today, it can feel like bands are treated as interchangeable—join when it’s exciting, leave when it’s not, and move on to the next big opportunity. There’s nothing wrong with exploring new challenges, but we sometimes forget that strong bands take real commitment, continuity, and care.

When large bands accumulate far more players than they need (let’s be honest here), other excellent bands will and do struggle to field competitive numbers. We’ve even seen iconic bands forced to take seasons off or lose key sections. Two recent collapses are a huge red flag. These situations don’t strengthen the community; they thin it.

The RSPBA’s role should be about supporting fair and healthy competition, and setting reasonable guidelines around maximum numbers could help maintain balance. This isn’t about limiting excellence—great bands will remain great. It simply ensures that success comes from quality, not quantity.

At the end of the day, the cream will still rise, and a more balanced ecosystem benefits everyone who loves this music. Everyone involved is a stakeholder and custodian. We should never allow a war of attrition to be a major factor in determining who is best. It is nothing short of self-sabotage.

Scott is right. I would extend the sport example. Not only limit the number of players on the field but also limit the number of players allowed in the clubhouse. Encourage the redistribution of fly-in talent. i.e. in the case of the Pipe Section, 22 Pipers on the field, from amongst say only the 26 named on the Band’s associated Competing Roster. (Something proportionately the same for the backend : organizations with bands in multiple grades would have rosters associated with each band.)